Acoustic Study of Broad-winged Hawks

Posted on in In the Field by Natia Javakhishvili, MS student and HMS Research Associate

In mid-May, right after finishing my second semester of grad school, I moved out of my apartment, loaded my belongings in the car, and drove to Pennsylvania to start my field work studying the vocalizations of nesting broad-winged hawks. Research on birds of prey has always been an area of interest for me. Back home in Tbilisi, Georgia, I was the director of SABUKO (Society for Nature Conservation, a local partner of Birdlife International) and spent my days trying to conserve an under-studied species, the eastern imperial eagle. However, after seven years in this position I decided to move to the U.S. to receive a master's degree in conservation biology at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

As conservation biologists, one of our main goals is to assess the response of species to changes in the environment, for which we study the size and distribution of their populations. Despite high ecological importance, the broad-winged hawk and other forest raptors are rarely included in the list of indicator species. This is likely attributed to their secretive nature and difficulty finding their nests, which are often placed high in the canopy and camouflaged once leaf out occurs.

For my master’s research I am using acoustic monitoring, more specifically autonomous recording units (ARUs), to monitor broad-winged hawk nests across Pennsylvania and to collect vocal recordings of nestling broad-winged hawks, which are absent from sound libraries. For the latter, I plan to develop a model that automatically recognizes nestling vocalizations, which can hopefully be used in the future to detect broad-winged hawks and their nests and to measure nesting success on a large geographic scale.

The main advantage of acoustic monitoring with ARUs, compared to the traditional field observations, is that they can be programmed in advance to record sound at desired time intervals and can record sound at fairly great distances. The longer duration of recordings is particularly important in the case of birds of prey, as their vocal activity occurs at unpredictable times during the day and mainly represents a certain behavior.

After my first few weeks in the field searching for broad-winged hawk nests in the Pocono Mountains and Allegheny National Forest (with the support of Scott Stoleson, a wildlife biologist at the US Forest Service), we confirmed 6 active nests. Spotting a raptor nest is probably one of the best feelings—a mixture of accomplishment and happiness. As soon as you see them, you will forget the weeks hopelessly spent in forests or swamps, hiking in impenetrable mountain laurel patches and suffering allergy attacks that are triggered frequently by pollen!

But my time to find additional nests was running out. Perhaps, if someone asks me what is one of the most important components of collecting data for a master's thesis, I would say that it's a lot about partners and people willing to help. I received ARUs and training in classifying recordings from my master’s committee members at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and University of Pittsburgh, and when I had trouble locating nests, I reached out to Drs. Laurie Goodrich and Rebecca McCabe to partner with Hawk Mountain’s Broad-winged Hawk Project to add nests from southeastern Pennsylvania to my sample. With the assistances of Hawk Mountain staff, field assistants, and volunteers, we deployed and monitored ARUs at 15 nest sites.

Once chicks hatched in early June, I spent time observing nests at Hawk Mountain and the surrounding area to document behavior and their associated vocalizations. Early in the nestling period, the nests I watched were very quiet, with almost no noise coming from the chicks. As the chicks developed, more sounds started to come from the nest. And now after hours of observing broad-winged hawk nests, I can say that chicks are quite vocal—often vocalizing as they beg for food, alarm the parents, or express excitement when prey is being delivered.

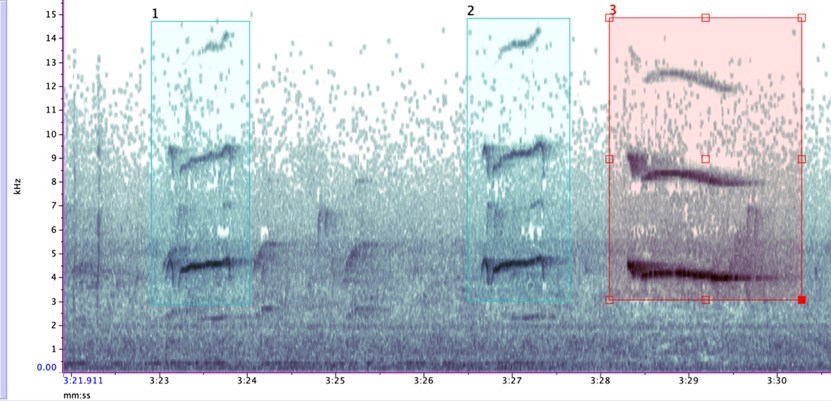

My observations continued into July, when chicks were already starting to jump to branches above the nest or fly to nearby trees. Now knowing what their sounds look like from the digital spectrograms, I could already recognize most of the chicks by hearing and distinguishing them from the adult calls. It is becoming obvious that acoustic studies of forest raptors can be used for not only locating nests and measuring their success, but also for quantifying food delivery rates or alarming the threats. Despite my progress with documenting and recognizing these calls, I am still in the process of annotating chick sounds from the recordings, and the results from my master’s research will come later this year.

Hawk Mountain's long-term research on broad-winged hawks began in 2014 and seeks to understand their full life cycle ecology and why broadwings are declining in some parts of their range. We thank generous private donors and Hawk Mountain Members for their support. You can support broadwing research like this by adopting a broadwing.