The Cooper's Hawk is a crow-sized accipiter or "bird hawk."

Accipiter cooperii

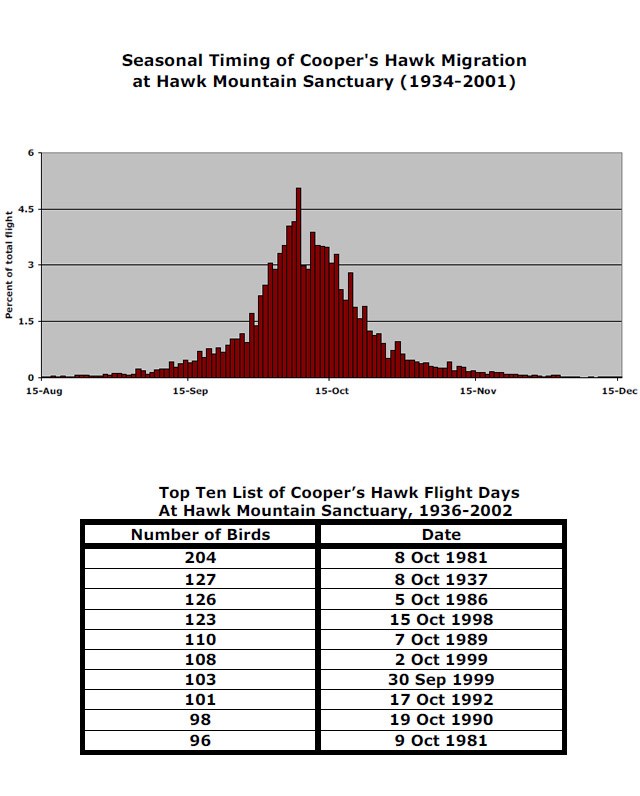

67-year annual average: 337

1992-2001: 739

Record year: 1,118 (1998)

Best chance to see: Early to mid-October.

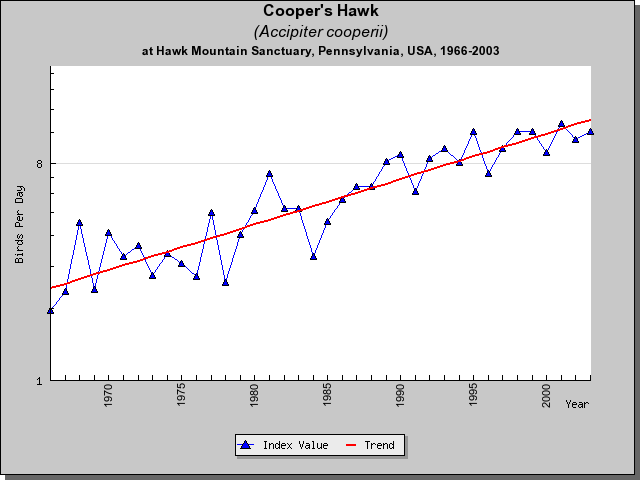

Longterm trends: Decreased from 1930s through mid-1960s, increasing since late 1960s.

A.K.A. Coop, Blue Darter

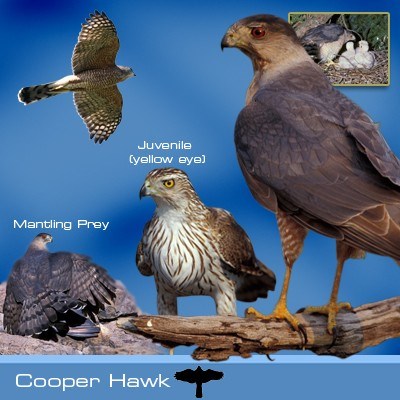

Field marks: Slender, crow-sized accipiter, with short, rounded wings and a long, rudder-like tail rounded at the tip. Juveniles are brown above and light underneath with dark streaking. Adults are grayish above and light underneath with rufous barring.

Flight behavior: Typically migrates alone. Soars, but frequently flaps and glides while migrating. Slightly more elongated silhouette than Sharp-shinned Hawk, with relatively larger head and longer tail, and slower, more deliberate wing-beat. Tail slightly rounded.

What Size is a Cooper's Hawk?

- Wingspan2'4"-2'-10"

- Length15"-18"

- W-L ratio1.9:1

- Weigth10-24 oz

Raptor Bites

- Belongs to the family Accipitridae, a group of 24 species of hawks, eagles, vultures, harriers, and kites.

- Named for William Cooper, a New York scientist whose son James is the namesake of the Cooper Ornithological Society.

- Closely resemble, but are larger than Sharp-shinned Hawks (Accipiter striatus).

- Cooper’s Hawks eye color changes from bluish-gray in nestlings, to yellow, in young adults and then to red in older adults.

- Females often weigh 35% more than their mates.

- Were highly persecuted earlier this century, when an estimated 30-40% of all first year birds were shot annually.

- Although they are common in some areas in the west, Cooper’s Hawks were listed as endangered, threatened, or of special concern in 16 eastern states as recently as the early 1990s.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

The hawk is a crow-sized accipiter that occurs in southern Canada, the United States, Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. One of three North American Accipiters or “bird hawks,” the Hawk is larger than the Sharp-shinned Hawk and smaller than the Northern Goshawk. Like other members of the genus Accipiter, the Cooper’s is well-adapted to forested habitats. The species has short, rounded wings, and a long tail, features that enable it to maneuver adeptly and to hunt in areas of dense cover. These Hawks are secretive during the breeding season, and individuals are most easily observed on migration.

Historically, raptors were labeled as “good” or “bad” depending on their dietary preferences, and North America’s three Accipiters were considered bad hawks. In the past, many people kept free-range chickens that made them vulnerable to predation, and these Hawks were a threat to poultry. The more conspicuous Red-tailed Hawk was often blamed for the more secretive Cooper’s Hawk’s predation.

Identification

Two distinct plumages: adult and juvenal. Adults have blue-gray upperparts and white underparts with rufous barring. Their tails have a series of alternating dark- and light-gray bands and a white tip. Adults also have dark crowns that contrast with their lighter-colored napes, and have yellow irises that darken with age, first to orange, and then to red in older adults. Juveniles have brown upperparts, and cream-colored underparts with reddish-brown streaks on their breast and belly. Females are as much as one third larger than males overall, and individuals from western North America generally are smaller than eastern birds. Overall, the hawk is a larger version of the Sharp-shinned Hawk, and separating these two species in the field can be difficult.

Although differentiating males from female Sharp-shinned Hawks is particularly challenging because the two are similar in size, there are several slight differences. Cooper’s Hawks have rounded tails, whereas Sharp-shinned Hawks have squared-tipped tails. In flight, the head of the Cooper’s Hawk projects well beyond the leading edge of its wing. Sharp-shinned Hawks tend to fly with their wrists thrust forward and with their heads barely protruding beyond the wrists. Cooper’s Hawks, therefore, appear “larger-headed” than Sharp-shinned Hawks. The silhouette of a Cooper’s Hawk in flight is sometimes described as a “flying cross” whereas that of the Sharp-shinned Hawk’s is said to resemble a “flying mallet.” The more robust Cooper’s Hawks is more stable in flight than the Sharp-shinned Hawk. Although both species show the typical accipiter flight pattern -- a series of three to six quick wing beats interspersed with brief periods of gliding -- the Cooper’s Hawk flaps with more deliberate and deeper wingbeats than the Sharp-shinned Hawk.

Breeding Habits

These Hawks nest in deciduous, mixed-deciduous, and evergreen forests, as well as in suburban and urban environments. Compared with Sharp-shinned Hawks, Cooper’s Hawks tend to nest in more open areas that have older and larger trees.

The species builds stick nests that are 61-71 cm across. Most nests are placed in a main crook of the tree or on a large, horizontal branch against the trunk, usually in a well-concealed location in the upper part of a tree. Raccoons and Great Horned Owls are the most common predators of eggs and nestlings.

Although pairs typically return to the same nesting area year after year, these Hawks usually build a new nest annually. Replacement clutches are sometimes laid if the first clutch is lost before or at the beginning of incubation. The species usually lays three to five eggs. Incubation takes 30-36 days, and the female does almost all of the incubating. After the eggs hatch, the female broods the nestlings continually for the first 14 days. While the female remains at the nest, the male provides food for her and their young. The female feeds the nestlings and the male usually delivers prey to her. If the female is away from the nest when the male returns, he will drop off food at the nest but will not feed the young.

Young fledge when they are 27-34 days old. Smaller males develop faster and leave the nest earlier than larger females and, overall, western birds appear to fledge sooner than eastern birds. For 10 days after they leave the nest, the young continue to return to the nest to roost and for food. The young remain near the nest and close to each other for at least five to six weeks. During this time, young Cooper’s Hawks gradually begin to hunt on their own.

Feeding Habits

Cooper’s Hawks hunt both from perches and on the wing. Hunting perches usually are situated in dense cover. Individuals typically conceal their approach and catch their prey by surprise while flying low to the ground, and using vegetation for cover. Once potential prey is detected, these Hawks usually attack with a sudden burst of speed. The species is persistent when chasing prey, and will pursue mammals on foot. Individuals sometimes submerse and drown their prey in lakes and ponds. Avian prey are typically plucked before being eaten. During the breeding season, prey are plucked at traditional plucking posts within the pair’s territory. At other times of the year, Cooper’s Hawks often pluck their prey at the capture site. Both the male and the female cache surplus food on branches near the nest during the breeding season.

The species feeds primarily on small- to medium-sized birds and mammals. Songbirds and gamebirds are the main types of avian prey consumed, and rodents are the most frequently taken mammals. Prey include American Robins, Blue Jays, European Starlings, Northern Flickers, and Eastern Chipmunks. In addition to mammals and birds, Cooper’s Hawks also take reptiles, amphibians, fish, and insects.

Migration

The Cooper’s Hawk is one of 26 North American raptors that are partial migrants.

Northern populations are more migratory than southern populations. Cooper’s Hawks from eastern North America overwinter in the central and southern United States, while individuals from western North America overwinter in central and southern Mexico.

When migrating, Cooper’s Hawks alternate between powered and soaring flight. Like other raptors, Cooper’s Hawks begin migrating across a broad front, but tend to concentrate along leading lines as they fly south, using updrafts and thermals to reduce energy costs. They usually avoid long water-crossings. At Hawk Mountain, the largest flights of Cooper’s Hawks are seen on the days following the passage of a cold front. At such times northwest winds create updrafts along the ridgeline. Cooper’s Hawks tend to migrate at higher altitudes when winds are light than when winds are strong.

The species generally migrates alone. In autumn, juveniles migrate earlier than adults, and within both age classes females migrate before males. In spring the reverse occurs: adults migrate before juveniles, and males migrate earlier than females. One hypothesis proposed to explain these age differences suggests that juveniles track the movements of their avian prey more closely than adults. In spring, adults are said to migrate earlier than juveniles because they are in a hurry to return to their breeding grounds.

Because Cooper’s Hawks are difficult to observe and census during the breeding season, migration counts serve as an important means for determining population trends. Numbers of Cooper’s Hawks at Hawk Mountain have increased recently: the Sanctuary’s long-term average autumn count (1934-2002) is 337 whereas the average for the past 10 years (1993-2002) is about 700. At North Lookout, peak numbers of Cooper’s Hawks are observed in early October when the chance of seeing at least one Cooper’s Hawk each day is 86%.

Conservation Status

The current population of this wholly North American species is estimated to be between one-hundred thousand and one million birds.

In the past, direct persecution significantly affected the Cooper’s Hawk. In eastern North America in the 1930s, for example, mortality from shooting was estimated at between 28%-47% for first-year birds. Like other Accipiters, Cooper’s Hawks did not receive legal protection from persecution in most states until well into the 20th Century.

During the middle of the 20th Century, Cooper’s Hawks were threatened by the widespread use of organochlorine pesticides including DDT. When Cooper’s Hawks consume prey containing DDT, the pesticide eventually accumulates in the species’ fatty tissues and causes eggshell thinning. Populations of Cooper’s Hawks declined during the DDT era, but rebounded following a ban on the widespread use of the pesticide in 1972. The numbers of Cooper’s Hawks increased dramatically in the 1980s and 1990s.

Currently, the species is common in many areas of the western United States, and many regional populations are increasing.

| BWHA Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | 4.1 | <0.0001 |

| 1974-2004 | 4.1 | <0.0001 |

| 1980-1990 | 4.1 | <0.0001 |

Cooper's Hawk Reading List

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin

Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton

Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian

Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

ROSENFIELD, R.N. AND J.BIELEFELDT. 1993. Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperi).

No. 75 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

SNYDER, N. AND H. SNYDER. 1991. Raptors: North American birds of prey.

Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minnesota.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New

York.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American

raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California.

WHEELER, B.K. 2003. Raptors of eastern North America. Princeton University Press,

Princeton, New Jersey.