Red-shouldered Hawks are slender, forest-dwelling Buteos.

Buteo lineatus

67-year annual average: 274

1992-2001: 293

Record year: 468 (1958)

Best chance to see: Late October.

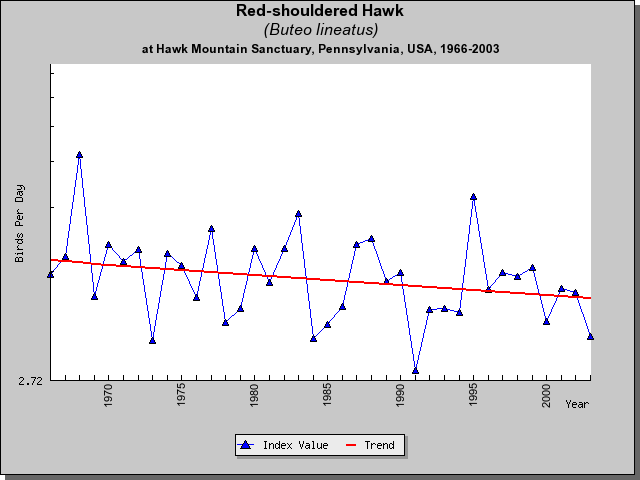

Longterm trends: Decreased 1950s-1970s; relatively stable in 1980s and 1990s.

A.K.A. Red Shoulder

Field marks: Slender, crow-sized, relatively long-winged buteo, with red shoulder patches and crescent-shaped, seemingly translucent, wing panels. The dark and white striped tail is relatively long for a buteo. Juveniles are light underneath with dark streaking; adults have rufous barring.

Flight behavior: Typically migrates alone, although small flocks occasionally occur during peak migration. Soars, and alternately flaps and glides while migrating. Graceful, butterfly-like flight pattern.

What Size is a Red-shouldered Hawk?

- Wingspan3'2"-3'6"

- Length1'3"-1'7"

- W-L ratio2.4:1

- Weight1.1-1.9 lbs

Raptor Bites

- Red-shouldered Hawks are part of the family Accipitridae, which includes 224 species of hawks, eagles, vultures, harriers, and kites.

- Are daytime ecological equivalents of Barred Owls (Strix varia).

- Because of forest fragmentation, Red-tailed Hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) have replaced Red-shouldered Hawks in many parts of eastern North America.

- Sometimes compete with Broad-winged Hawks (Buteo platypterus) for nest sites.

- Have long rudderlike tails that allow them to turn quickly while pursuing prey.

- Are easily identified by a crescent “window” on their wings.

- Red-shouldered Hawks often feed on aquatic and semi-aquatic animals, including small fishes and frogs.

- Are quite vocal when courting. Their calls are often mimicked by Blue Jays (Cyanocitta cristata).

- Are found in two separate regions of North America, California and the eastern United States.

- Have paler feathers in Florida than in the northern United States.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

Redshoulders are slender, forest-dwelling Buteos that occur throughout much of the eastern United States and southeastern Canada, as well as in Oregon, California, and Mexico. The species tends to prefer large, mature, contiguous, mixed deciduous coniferous forests with open understories. Red-shouldered Hawks favor wet forests, particularly bottomlands near streams, rivers, swamps, and marshes. In the early 1900s the Red-shouldered Hawk was the most common Buteo in New England. Twentieth Century logging of mature forests, which benefited the Redtailed Hawk, reduced the amount of habitat suitable for Red-shouldered Hawks. Loss of large forests also fostered more frequent competition with, and predation by, Great Horned Owls.

Identification

Red-shouldered Hawks are intermediate in size between the smaller Broad-winged Hawk and the larger Red-tailed Hawk. Like other Buteos, Red-shouldered Hawks have long, broad wings and soar with their tails fanned. The species, however, is lankier and has a proportionately longer tail than other Buteos. In active flight, Redshouldered Hawks sometimes appear Accipiter-like and fly with a series of quick wingbeats followed by a short glide. When soaring overhead, especially when backlit, the species displays translucent, crescent-shaped patches near the tips of its wings. - Red-shouldered Hawks have brownish heads and backs, reddish breasts, rufous shoulder patches, and black and white flight feathers. Their tails are black with several narrow white bands. Juveniles are mostly brown from above and have cream-colored underparts with brown streaking. They are most heavily streaked on their chests. The Red-shouldered Hawk is fairly vocal, especially during the breeding season. Its typical call is a loud Kee-aah scream, which is often mimicked by Blue Jays. Red-shouldered Hawks differ slightly in appearance across their range, and five subspecies are recognized.

Breeding Habits

Red-shouldered Hawks are monogamous, and most individuals breed for the first time when they are two years old. Pairs usually remain in the same territories and reuse the same nest-sites for many years. Courtship lasts about 18 days, and during this time “circling flight” and “sky-dancing” displays are performed. In their circling flights, pairs soar together with their wings spread and their tails fanned. The male and the female soar toward and then away from each other, and one member of the pair sometimes soars higher than and dives on the other. Males “sky-dance” by repeatedly making a steep dive and then soaring upward in a spiral. Red-shouldered Hawks are particularly vocal prior to incubation, and they call repeatedly while engaged in courtship flights. - Red-shouldered Hawks usually nest in deciduous or mixed deciduous-coniferous forests. Nests are typically built at a crook of the main trunk in deciduous trees, more than halfway up the tree but within the canopy. Both males and females are involved in nest construction, and the process takes one to five weeks. Nests are 45-60 cm in diameter, 20-30 cm deep, and are constructed from sticks, strips of bark, dried leaves, lichens, conifer sprigs, and Spanish moss.

Red-shouldered Hawks lay one clutch per year. Replacement clutches are sometimes laid if the first clutch is destroyed. The species usually lays three to four eggs. Nest success varies overall, and the timing of nesting and food availability are important factors. Predation is also a threat to nesting success. Great Horned Owls and raccoons prey on eggs, young, and adult Red-shouldered Hawks. Red-tailed Hawks, Peregrine Falcons, martens, and fishers are also potential predators. - The eggs are incubated for about five weeks, mainly by the female. Incubation begins before all the eggs are laid; therefore, clutches hatch asynchronously. After the eggs hatch, the female broods the nestlings continually for a week, but thereafter spends increasingly less time brooding. While the female remains at the nest, the male is responsible for providing food. The male brings food to a spot near the nest and then calls for the female, who accepts the prey and delivers it to the young. Beginning several weeks before the young fledge (leave the nest), both the male and the female hunt for food for the young. The nestlings are able to tear apart food when they are about 18 days old. Young fledge when they are between 35 and 45 days old. By the time they are seven to eight weeks old, the fledglings begin to capture their own prey. At first they catch mainly insects, but after several weeks they start to catch vertebrates as well.

Feeding Habits

Red-shouldered Hawks are generalist and feed on many types of prey including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Crayfish serve as an important food source, particularly in the southeastern United States. In much of eastern North America, Eastern Chipmunks and Meadow Voles are the main prey. Overall, adults most frequently bring back mammals to feed the nestlings. Although the species sometimes hunts on the wing, Red-shouldered Hawks are chiefly perch-hunters. When hunting in open areas, Red-shouldered Hawks sometimes hunt from a low, coursing flight similar to a harrier.

Migration

The Red-shouldered Hawk is one of 26 North American raptor species that are partial migrants.

In the East, individuals from the northern half of the species’ range are migratory. In the West, most populations are sedentary. Red-shouldered Hawks are short- to moderate-distance migrants, with most individuals traveling distances between 300 km and 1,500 km each way. The species follows leading lines, migrating along inland ridges and coastlines. Larger numbers of Red-shouldered Hawks are counted at coastal watchsites than at inland sites. Juveniles often precede adults on migration in autumn, whereas adults precede juveniles in the spring. Red-shouldered Hawks typically migrate alone, although they sometimes form small flocks of three or more birds. The species usually avoids crossing large bodies of water. While migrating, Red-shouldered Hawks are observed in soaring, gliding, and flapping flight. - At Hawk Mountain, about 300 Red-shouldered Hawks are counted each autumn, with the peak occurring in late October. Red-shouldered Hawks that are counted at the Sanctuary usually spend the winter in the southeastern United States, although some travel as far south as Mexico.

Conservation Status

The current world population of Red-shouldered Hawks is estimated to be 100,000 birds.

Despite regional variation, the number of Red-shouldered Hawks appears to be declining overall. Many populations have decreased due to the clearing or draining of lowland forest habitats. Great Horned Owl predation is a common natural threat. People, however, directly and indirectly pose a threat to the species as well. Habitat loss has caused population declines and continues to affect Red-shouldered Hawk populations. Habitat changes enable potential predators and competitors to more easily displace or predate redshoulders. Historically, human persecution, especially shooting at well-known migration spots, was a source of mortality. Shooting is no longer a serious threat to the species. Human disturbance close to nests sometimes causes nest failures, and collisions with automobiles, as well as exposure to environmental contaminants, kill some birds. Between the late 1940s and the early 1970s, the widespread use of the pesticide DDT caused eggshell-thinning. However, eggshell-thinning was less severe for Red-shouldered Hawks than for many other raptor species, and whether or not the species’ reproductive success was compromised by this pesticide is unclear.

| BWHA Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | -0.6 | 0.11 |

| 1974-2004 | -0.6 | 0.11 |

| 1980-1990 | -0.6 | 0.11 |

Red-shouldered Hawk Reading List

CROCOLL, S.T. 1994. Red-shouldered Hawk (Buteo lineatus). No. 107 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington,

D.C. DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

SNYDER, N. AND H. SNYDER. 1991. Raptors: North American birds of prey. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minnesota.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California.

WHEELER, B.K. 2003. Raptors of eastern North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.