A Sanctuary Legend

Posted on in A Year in Stewardship by Noah Rauch, Sanctuary Steward

If you knew Jim Brett, you know he had a story to tell, and usually a good one at that. People live on through more than just stories, though. They live on through the things they helped to create and through the impact they made while they were here.

Soon before Jim passed on, some colleagues told me they were going to visit with him. When I heard this, I smiled, let them know to extend a hello from me, and carried on to the next task. I can't quite recall what transpired for me after that conversation. I’m sure it was a few of the hundreds of things that could take place at the sanctuary on any given day. I do remember thinking of Jim though. It had been a long time since I’d last spoken with him, but it didn’t really feel that way. I remembered seeing Jim and Dottie at the fire company social hall, out with my grandmother and their friends socializing and enjoying our local community. I remembered driving Jim home after a presentation he attended on the mountain, taking the long way around and talking about the natural history of the area and local landmarks. I remembered the letter he wrote encouraging me to stay the course when I had hit wits end with college. I remembered an old copy of Bird Watchers Digest my dad handed me one afternoon when he was finished doing some contract work at the Bretts house. “Jim wanted you to have this” he said. “There’s an article about him in it that he thought you might want to read.”

When I got home from work that day I rooted through my bookshelf, found that copy of Bird Watchers Digest, and re-read the story about Jim. The amount of impact it had on me now in comparison to when I’d first read it was evident. It tells parts of his story both before and during his time on the mountain, and so much of it resonated with me on a personal and professional level.

I’ve read the article probably a dozen times since we lost Jim and felt compelled to share it with others that would care to read it. It was written in 1984 for the sanctuarys 50th anniversary. In commemoration of our 90th anniversary this year, and in Jims honor, I transcribed the article to post here. If you have the time, it’s well worth the read. One of the last lines in the piece is a quote from Jim where he says, “I want to develop in others the love affair that I have for the land, its people, and its natural history.” He did just that, for me, and for countless others. He will be dearly missed by so many, but his legacy lives on.

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary's Jim Brett

By Durrae Henry

Bird Watchers Digest - 1984

The mountain, the birds, the people who visit this famed Pennsylvania site – are all part of his job.

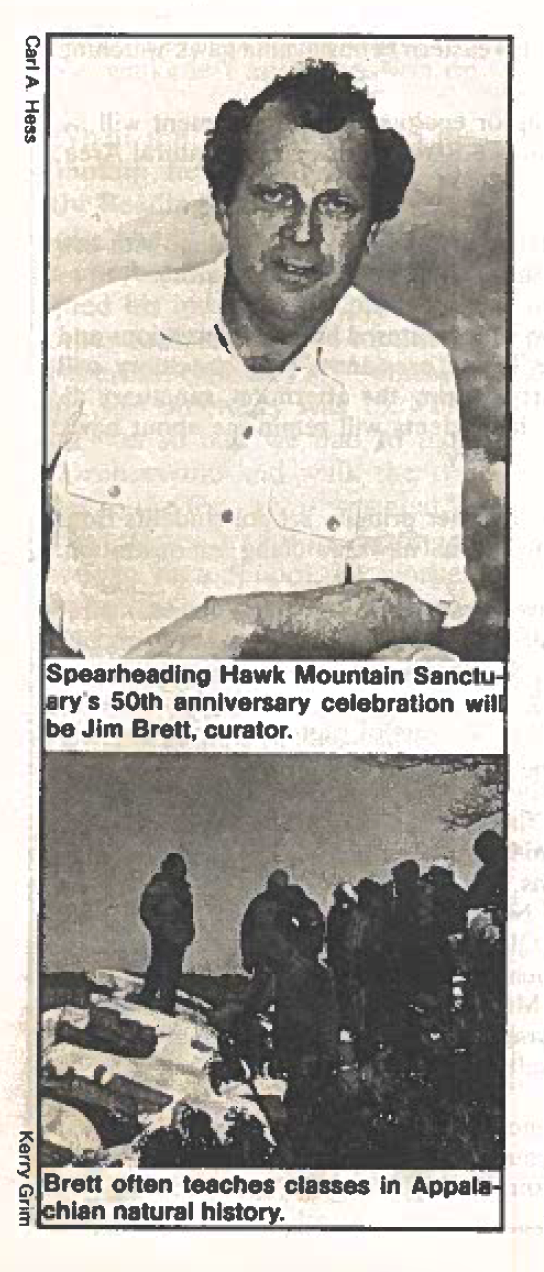

“I've never had a course in ornithology – as an ornithologist, I’m a fraud,” says Jim Brett who, as curator of Pennsylvania's Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, works with birds every day. We’re in the headquarters seated near a huge picture window that looks out over the numerous feeders that today have attracted many local passerines. “We probably shouldn't use the term ‘curator’ - ‘curator’ is a fossil. You usually think of a curator as someone who works in a museum and is responsible for a collection. I’m responsible for a collection alright, but they’re not dead, not when you’re managing 60,000 people a year.” Brett prefers “interpretive guide,” which is what he's been for the past 12 years at the sanctuary. He was appointed curator in 1982 “probably because I was the most logical choice since I’d been here for so many years as assistant curator.”

The headquarters is an aesthetically pleasing, earth-bermed building, so completely blending in with its surroundings that the entrance is the only evidence of its existence. Situated on the Kittatinny Ridge, the sanctuary began as an environmental battleground where conservation groups, working to change the popular assessment of raptors as “varmints” needing eradication, managed, through the efforts of Rosalie Edge, to buy 1,400 acres of land in 1934 as a refuge. For 32 years the late Maurice Broun, author of Hawks Aloft, was its legendary curator, building the sanctuary's reputation as the best place in North America to view thousands of migrating hawks, falcons, and eagles. He was succeeded in 1966 by Alex Nagy, who continued to develop the sanctuary's programs, serving as curator until 1982. Today, Hawk Mountain Sanctuary is host to thousands of birders, leaf watchers, and casual passersby. It’s not unusual to see hikers with full gear mingle with people dressed in their Sunday best.

Brett was originally hired to implement summer courses for teachers in techniques of nature education and to set up field courses in natural history, botany, and Appalachian history. He also established college intern and volunteer programs. “I’ve always been excited about these two programs. We began with one intern and now have ten a year, the only requirement being that they appreciate nature and like people. They are our ambassadors when they leave here. The volunteers are equally important. If it weren't for them and the regulars, the sanctuary wouldn't be where it is today. They do the hawk count, maintenance, parking, and mailings – they spread the word.”

A Gene Wilder look-alike with curly hair, twisted grin, and the same intense look, Brett frequently uses the word “neat” to express his enthusiasm and excitement. His striking blue eyes are the same color as his chambray work shirt and faded jeans. Although he’s dressed casually, there's nothing casual about the way he views his job. The mountain is as much his family as is his wife, Dottie, and their three children.

His interest in ornithology had a dubious beginning. His grandfather who lived with his family in Easton, Pennsylvania, raised chickens for bird fighting. Jim and his brother learned how to get the birds ready for fights and how to care for those that were injured. “Of course, it was all highly illegal, but my grandfather came from a part of England where it was acceptable. My mother hated the whole thing and had a rule that we couldn't watch, but we’d sneak out anyway. It's a contradiction, I know, but my grandfather was very nature-oriented and would often take me for walks in the woods, pointing out things of interest. I was only six or seven, but those walks left an impression on me.”

When Jim moved closer to the mountain, he joined a nature club at the Reading Museum, where Earl Poole, one of the first members of the sanctuary’s board of directors, piqued his interest in raptors. His mother took him to the mountain for the first time in 1949 – Jim was nine; and the sanctuary was 15. “The road was so bad we had to park in Drehersville and walk the two miles to the top, but it was neat.”

His interest in raptors continued when, in high school, he worked part-time as a gravedigger. He and a friend dug at night by lantern because it was cooler, but also because they could watch long-eared owls in the nearby woods. “We used to rest a lot to watch the owls and weren't real conscientious about digging; in fact, one day we held up an entire funeral that was already in progress because we hadn’t dug the hole deep enough for the vault.”

In high school and college, he was a disastrous student, enjoying the field work but not doing so well in class. Today, he’d still rather be outdoors teaching students and mingling with the people and hawks on the lookouts, but he’s become bogged down with more administrative duties than he’d like. “This whole thing has snowballed into something that’s hard to handle at times. We want the mountain to be a worthwhile experience for everyone. We developed the on-ground interpretive program so that when people come here they don’t just walk to the lookout, see a panorama and a few hawks, and leave without knowing where this place has come from, the road it has traveled up to the present, and where it is going.”

Brett didn’t seriously become interested in educating children about nature until he got his first job teaching – seventh grade English. “I wanted biology, but there weren’t any openings until a year later.” He was invited by the National Science Foundation to go to a small college near San Fransisco to help write a textbook for a curriculum being developed in ecology. He was one of 16 people chosen worldwide to write the lab manual. While there he became an active hiker and increasingly more involved in the outdoors. When he came home to York County, he started the Northeastern High School Ecology Club and established a nature center with an initial enrollment of four or five students that quickly expanded to 30.

He enjoys people and working with groups, even the large crowds that flock to the mountain every October. A typical fall weekend will bring 3,000 people a day, but Jim doesn’t mind. “I feel fine. I do really. I enjoy it immensely.” The volunteers and staff were driven to tears of frustration, but Jim’s never had what he’d call a bad day – strange maybe, but not bad. He has always taken things in stride.

He was offered another fellowship in Aspen, Colorado, where he met Bob Lewis, the man responsible for the way Jim now thinks about education. “His programs were unique – a hands on approach that really turned me on. We developed the first nature trail for the blind, which excited me so much that when I came home, I started a second trail at the nature center. There are now more than 150 trails in the country. The kids were really responsible for it and got recognition from President Lyndon Johnson.”

While he was at the nature center, he was approached by a man from Cornell University who had been hired to do survey work at the Limerick nuclear power plant. He asked Brett if he knew anything about aquatic insects. “I didn’t know a thing, but said ‘Hell yeah, I know a lot about aquatic insects.’ I walked into a room with a whole wall filled with bottles of samples. When I opened up that first bottle and saw this mess in front of me, I wondered what I had gotten myself into. In the daytime I floated the river and took samples. It was wonderful, but at night I had to go back and face this mess, and for weeks on end from five at night until two in the morning, I learned about insects. We eventually became the SWAT team on aquatic biology. We got a great reputation and were called on to hold seminars and teach aquatics.”

He hired students from the high school ecology club and began his own aquatics lab, but after a while the students were floating down the river, and Brett was doing all the lab work. He missed the outdoors. “I thought, ‘This is crazy. I’m teaching college and high school and researching five nights a week. I can’t do this the rest of my life,’” and decided to apply for an opening at Hawk Mountain. During the interview, he was asked if he knew anything about birds of prey, “but I couldn’t lie. This was too important. I told them if I can learn 30 species of insects, I can learn 14 species of raptors. Little did I know.” He had his heart so set on this job that he quit all his others before he found out he was hired. “That didn’t make Dottie very happy.”

His first official duty at the mountain was a Saturday night lecture. The common room was filled to capacity, and without knowing the inside operation of the movie screen, he pulled the thing “right out of the ceiling. But everyone was kind about it.” He managed to get through that first season with the help of Dick Sharadin whom Brett considers to be the most knowledgeable person in hawk identification and behavior.

Jim’s life is never his own when he’s on the mountain. He and Dottie managed to get a few days alone for the first time in 20 years only a few months ago. Their phone rings at all hours of the night with calls concerning the next days flight. Jim is a 24-hour-a-day security force and medivac team. He’s often called upon to pull people out of ditches in the winter or to put up with stragglers stumbling in, in the middle of the night, looking for a place to stay.

He’s a one-man public relations team – active in the surrounding communities, past-president of the Kempton Fire Company, and chairman of the local planning commission – who has made it a personal mission to get close to the local people. “We have a neat community here. It’s like an extended family. When I came to the mountain, we were still blackballed,” he said, referring to the friction between the local hawk shooters and the restrictions of the sanctuary. “The day a local man came to the lookout for the first time was a hallmark. Here was a guy who had lived in Kempton all his life and who had shot hawks, but now felt differently.”

Brett was also thrilled the day a 92-year-old woman made it to the north lookout, a strenuous one mile hike, under her own power. It was the first time she had been there since she was eight, when her father brought her to see an eagle’s nest. He gets excited when the students he had 20 years ago bring their children to the lookouts. “There’s one fellow who comes for a week or two each fall for the golden eagles. He says the only time he can laugh all year is when he comes to Hawk Mountain. That makes me feel good.”

On days with slow flights, the people can be more interesting than the birds. Brett cited two American Indians who come for eagle and hawk feathers to use in their ceremonies, and the scientist from the People's Republic of China, on a visit to Washington D.C., who couldn’t wait to get to Hawk Mountain. “One day a bus of elderly ladies from New Jersey who had heard about our reputation for Broadwing's came to see for themselves. They pulled into the parking lot, and I pointed out a kettle directly overhead. As they all piled off the bus, the birds lost their thermal and came down – on the bus, on the fence, on the road; they were everywhere. The women couldn't believe it (neither could I) and left quite satisfied and immensely impressed. That could never happen again in a million years.”

Not all incidents are as pleasant as the one involving the ladies from New Jersey. Brett is strict about enforcing the sanctuary rules, and more often than he’d like has had to ask violators to leave. Offenses have ranged from violations of the prohibitions against alcohol, dogs, and blaring radios, to a Civil Air Patrol squad’s rappelling off the south lookout. “When something like that happens, I just deal with it; I don’t get uptight.”

He did get upset, however, when he came across a young boy carving his name on a tree, with his father's approval, even after he was asked to stop. Carving one’s name on a tree is an insignificant act to many people, but to Brett it’s indicative of our country's overall attitude toward nature. Having just returned from Israel, he couldn’t help comparing values and attitudes. “Their values are wonderful. Here’s a country surrounded by the enemy, and yet they are concerned with and have an incredible respect for nature, They built it all themselves and appreciate what they have. We as a country seem to think our resources are going to last forever. We’re more concerned with developing and the dollar.”

Could a job that some of us would hang up our binoculars for ever be boring? “No, though I do get bored easily; it’s evident in my hobbies. I used to work with stained glass, and I did build my own house, but I have to have something to put all my energies into, take it to the end, and go on to something else.”

Brett is 44; this year the sanctuary is 50. They’ve both come a long way, but there is still much to do. He ticks off a list: adding new programs, reprinting Feathers in the Wind, which is sold out, writing a sequel to Maurice Broun’s Hawks Aloft, and someday writing his own book. “We’re delegates to the International Council for the Preservation of Birds, for which we monitor the situation of endangered birds in North America. We have established credit courses with a local college, We’re working closely with Greece, Israel, and England on the preservation, conservation, and management of birds of prey. We need an organization specifically for birds; Audubon comes close but does have other interests. There are many people nearby who still don’t know where or what Hawk Mountain is. We have to reach these people and make them aware."

Brett loves people, the mountain, birds, and educating people. He’s a generalist, not a listener. He’s concerned about the relationship between birds and their environment – what it was, is, and is likely to become. “I want to develop in others the love affair that I have for the land, its people, and its natural history. I’m more a people person than a scientist or ornithologist. That’s what I am.”