Northern Harriers are slender, open-country raptors.

Circus cyaneus

67-year annual average: 228

1992-2001: 243

Record year: 475 (1980)

Best chance to see: Late October.

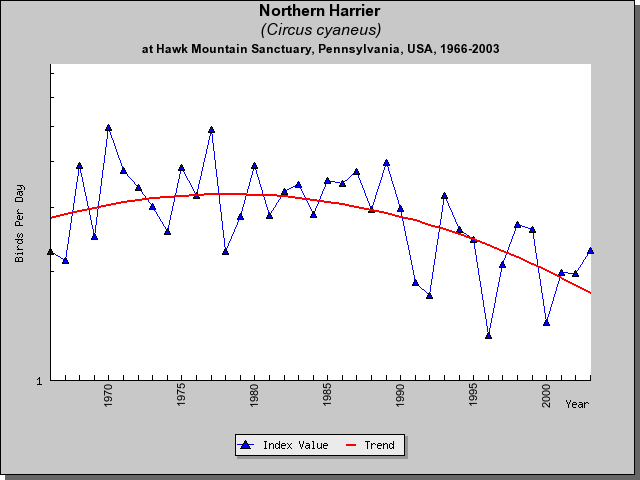

Longterm trends: Decreased during DDT-era; increased in 1970s; fluctuating since mid-1980s.

A.K.A. Marsh Hawk, American Harrier, Hen Harrier, Harrier, Gray Ghost (Adult males only)

Field marks: Slender, medium-sized raptor, with a white rump patch, and long, relatively narrow wings held above the horizontal in a dihedral. Juveniles and adult females are brown above, and cream (adults) to chestnut (juveniles) below, often with dark streaking. Adult males are gray with black wing tips above, and white, with faint rufous spotting below.

Flight behavior: Typically migrates alone. Soars, but more frequently flaps and glides while migrating, often at tree-top level. Occasionally rocks in flight like the Turkey Vulture. Sometimes migrates in light rain or other precipitation.

What Size is a Northern Harrier?

- Wingspan3'2"-4'

- Length1'6"-2'

- W-L ratio2.4:1

- Weight0.7-1.3 lbs

Raptor Bites

- Northern Harriers are part of the family Accipitridae, which includes 224 species of hawks, eagles, vultures, harriers, and kites.

- There are 13 species of harriers, worldwide.

- The Northern Harrier is the only harrier in North America.

- Northern Harriers have an owl-like facial disk that allows them to hunt by sound as well as by sight.

- All Northern Harriers have a white rump patch.

- Adult male Northern Harriers are gray above, adult females and juveniles are brown above.

- Northern Harriers fly with their wings in a slight dihedral to help stabilize their flight.

- Northern Harriers hunt almost exclusively on the wing for small mammals and birds.

- Male Northern Harriers often mate with two or more females in a single season.

- In winter, Northern Harriers roost communally on the ground, often together with Short-eared Owls (Asio flammeus).

- Northern Harriers appear to be declining in North America because of the loss of natural open habitats.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

The Northern Harrier is a slender, long-winged, low-flying, open-country raptor that is found throughout much of the United States and sub-Arctic Canada. Of the 13 species of harriers that occur worldwide, the Northern Harrier is the only one that occurs in North America. The Northern Harrier also occurs in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Across its range, the Northern Harrier prefers open habitats, including marshes and grasslands. Harriers typically nest on the ground, either alone or in loose colonies. Outside of the breeding season, harriers roost communally on the ground, sometimes with Short-eared Owls.

Identification

Northern Harriers have long wings, long and narrow tails, and owl-like faces. The species is lightly wing-loaded and often rocks in the wind like a Turkey Vulture while flying with its wings held in a dihedral or “V” above its back. Harriers have three distinct plumages: the largely light gray adult male, the largely light brown adult female, and the largely dark brown juvenal. In all three plumages the species has a conspicuous white rump patch. Adult males, which are sometimes referred to as the “gray ghosts,” are mostly gray above and whitish below with black trailing edges on their underwings and black wingtips. Adult females are mostly brown above with buffy underparts that are heavily streaked with dark brown. Juveniles are mostly dark brown above with cinnamon breasts and bellies. Females are 10-20% larger and weigh approximately 50% more than males.

Breeding Habits

Northern Harriers are both monogamous and polygamous. Polygamous males usually have two or three mates, although one individual is known to have attended seven females simultaneously. In polygamous situations, each female has her own nest, and the male tends to each female individually. Aerial displays and courtship-feeding rates appear to be the principal factors in a female’s selection of a mate. Females sometimes abandon their mates during nest building or courtship if the male fails to display enough or does not provide sufficient food. Males and females do not mate for life. Males usually return to the breeding grounds before females and begin aerial displays when the females arrive. “Sky-Dancing” is intense and more frequent in years when food is abundant, and males that display the most typically attract the largest number of females. Sky-Dancing involves a series of U-shaped, undulating flights at heights that range from 10 meters to 300 meters above the surrounding countryside, and that sometimes cover distances up to a kilometer or more. Males fly to potential nest sites at the end of their display, and interested females follow them. Although they often return to and nest in the same general area, Northern Harriers do not reuse the same nest site year after year. Harriers build their nests on the ground, almost always in open habitats. Either the male or the female selects the site and both help build the nest. Most nests are placed in areas of dense grassy or shrubby vegetation, and frequently in wet areas, to reduce the risk of predation. Nest construction takes from several days to several weeks. Pairs continue to add nesting material during incubation and, sometimes, until the nestlings are three to four weeks old. Harriers lay one clutch of four to six eggs annually. Replacement clutches are sometimes laid if the first clutch is destroyed. Incubation begins after the first egg is laid, and the nestlings hatch asynchronously. During the 30- to 32-day incubation period, the female tends the nest continually, leaving only to receive prey deliveries from the male, collect additional nesting material, and take short “exercise” flights. Nestlings are brooded continually for the first 12 to 14 days. Thereafter, the female spends less time at the nest during the day, but continues to brood the young at night for another two weeks. The male provides food to the female when she is at the nest. Males call as they approach the nest with prey and then pass the prey to the female in an aerial transfer. When the female is not at the nest, males sometimes drop food onto the nest, but they do not directly feed the young. Females mated to polygamous males typically receive less food from their mates than their monogamous counterparts, and such females often begin hunting earlier in the nestling period. As a result, nestlings in “polygamous” nests are more susceptible to predation. By the time the nestlings are two weeks old, they begin to walk and hop up to 15 meters from the nest. Young harriers take their first, short flights when they are four to five weeks of age. After fledging, the young typically roost near each other at night and spend most of their day on perches waiting for their parents to return with food. Siblings often fly together and chase each other, particularly when the adults return to the nest with prey. Parents transfer prey to their young in the air, and the first fledgling to intercept the returning parent usually receives the food. Parents continue to provide the fledglings with food for two to four weeks after fledging. Fledglings spend less than an hour each day hunting, and they seldom catch prey on their own before becoming independent.

Feeding Habits

Northern Harriers search for prey in open habitats, typically while flying close to the ground in buoyant gliding and flapping flight. The species prefers to hunt in open areas with mixed vegetative cover and tends to avoid areas with only short vegetation. Harriers rarely hunt while perched. In winter, individuals sometimes rob prey from each other. The harrier’s owl-like facial ruff and tendency to fly close to the ground allows the species to hear, as well as see, potential prey, and the species often locates its prey by sound. Adult males tend to be the most successful hunters, followed by adult females. Juveniles are decidedly less proficient hunters than adults. In summer, harriers feed on small- to medium-sized mammals (particularly rodents), as well as on birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. Mammals and birds comprise the majority of the species’ diet in winter, but the diets of individuals vary depending upon their location. In the northern portion of their range, voles comprise the majority of the Northern Harrier’s diet. Large prey are usually torn apart before being eaten. Small prey, including mice and insects, sometimes are swallowed whole. Harriers sometimes hide, or cache, surplus food, particularly during the breeding season.

Migration

The Northern Harrier is one of 26 North American raptors that are partial migrants. Harriers breeding in northern portion of the species’ range tend to be long-distance migrants. Like most raptors, Northern Harriers begin migrating across a broad front. Although individuals concentrate along corridors as migration proceeds, harriers are less likely to do so than are other species of raptors. As a result, the number of Northern Harriers counted at migration watchsites tends to be low, and the species rarely accounts for more than four percent of the total flight at most hawkwatches. Larger numbers of harriers are counted at coastal watchsites than at inland watchsites. Harriers are primarily solitary migrants and the species has a protracted migration, in both autumn and spring. During migration, harriers incorporate a mixture of flapping and gliding flight with little soaring, and they tend to fly closer to the ground than many other migrants. The species also migrates in adverse weather, including light rain and snow, conditions in which many other raptors do not migrate. Northern Harriers are one of only a handful of raptors that regularly fly long distances over water. About 230 Northern Harriers are counted at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary each autumn. The majority of the flight passes between September and November, with a modest peak in late October.

Conservation Status

The current North American population of Northern Harriers exceeds 100,000 birds. Overall, Northern Harriers appear to be decreasing globally and most declines are attributable to habitat loss. Suitable breeding and feeding habitat has decreased in many parts of the species range because of large-scale monotypic farming, farmland reforestation, and the extensive draining of wetlands for agriculture and other development. Prey availability decreases in areas due to overgrazing, the emergence of large crop fields and fewer fence rows, and with pesticide use. Agricultural machinery, early mowing, and livestock directly destroy nests. From the mid-1940s to the early 1970s, the widespread use of organochlorine pesticides including DDT increased pesticide levels in prey that harriers feed upon. When Northern Harriers consume prey containing DDT, the pesticide accumulates in the harrier’s fatty tissues and reduces reproductive success by causing eggshell thinning.

Many North American populations of Northern Harriers that declined during the DDT era rebounded following bans on the widespread use of the pesticide in 1972. Although Northern Harriers have largely escaped direct persecution in most of North America, they have been targets of persecution elsewhere. In Great Britain, where harriers are viewed as a threat to Red Grouse and other species of upland game, gamekeepers shoot adult harriers and destroy their eggs and nestlings.

| BWHA Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | 0.5 | .57 |

| 1974-2004 | -2.0 | <0.0001 |

| 1980-1990 | -1.3 | 0 |

Northern Harrier Reading List

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton

Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian

Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

MACWHIRTER, R.B. AND K.L. BILDSTEIN. 1996. Northern Harrier (Circus

cyaneus). No. 210 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds).

The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and The

American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New

York.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American

raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California