Black Vultures are one of the most abundant New World vultures.

Coragyps atratus

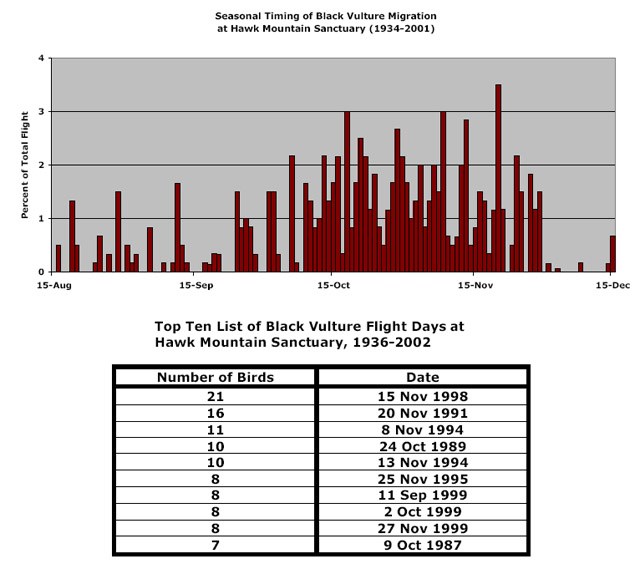

67-year annual average: 10

1992-2001: 46

Record year: 80 (1999)

Best chance to see: Late October.

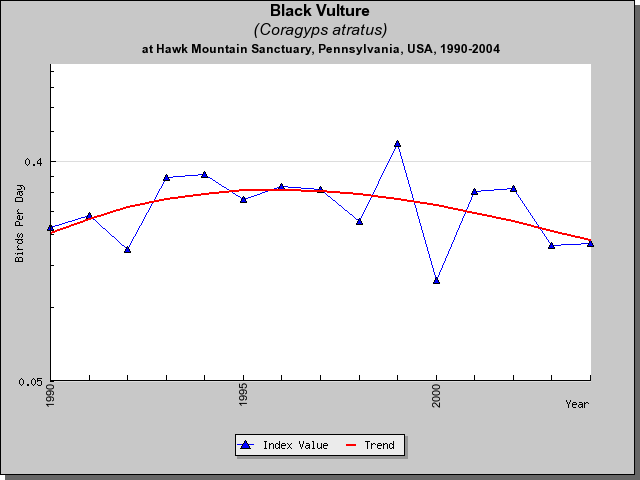

Longterm trends: Increasing, probably in response to northward expansion of breeding range.

Field marks: Large, heavy-bodied, carrion-eating, black bird, with short tail and broad plank-like wings tipped with white.

Flight behavior: Typically migrates in small flocks of up to several dozen birds. Soars extensively. Does not rock back and forth like the Turkey Vulture.

Click below to view flyers summarizing the black vulture's habitat and nesting behaviors, as well as guidelines for landowners that may encounter forest nesting raptors:

Black Vulture Habitat & Nesting Landowner Guide to Protecting Nesting Raptors

What Sizes is a Black Vulture?

- Wingspan5'

- Length2'-2'4"

- W-L ratio2.3:1

- Weight4.5-6 lbs

Raptor Bites

- Belong to the family Cathartidae, a group of 7 species of New World Vultures.

- Are the heaviest vultures in the Eastern United States.

- Black Vultures, which rarely flap in flight, have broad plank-like wings that allow them to soar in small thermals.

- Search for carrion exclusively by sight. As a result of the Turkey Vulture’s acute sense of smell, Black Vultures often follow Turkey Vultures to find food.

- Sometimes take live prey.

- Usually roost together in family units.

- Nest on the ground and on the floors of abandoned buildings.

- The range of Black Vultures has been expanding northwards since the 1950s.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

Along with the Turkey Vulture, the Black Vulture is one of the most abundant New World vultures. In North America, these Vultures are known to breed throughout the southeastern and middle Atlantic region of the United States and are often sighted in southeastern Canada. The species also breeds throughout Central America and much of South America. These Vultures typically occur in open or partly forested habitats, often in close proximity to human settlements. Recently, this species has expanded northward in the eastern United States. Presumably, greater numbers of these Vultures existed historically when waste disposal, ranching, and farming practices were less regulated. The Vulture is a highly gregarious species. Outside of the breeding season they often gather by the hundreds at communal roosts. Traditional roost sites, some of which are used for decades, often are occupied year-round. Other roosts are used seasonally in response to food availability. Roosts are thought to play an important role in the social lives of Black Vultures, both as places for juveniles and adult Vultures to interact, and as sites for foraging groups to assemble. There is some evidence that vultures find food by following conspecifics from roosts to carcasses. Turkey Vultures and Crested Caracaras often roost together with Black Vultures.

Identification

These Vultures have featherless dark gray to black heads and necks. The species appears black overall when perched, however conspicuous white patches near the wingtips are clearly visible in flight. The gray legs and toes often are stained whitish with excrement. Adult Black Vultures have dark bills with bone-colored tips and their heads and the upper half of their necks are dark gray and covered with wrinkles. Juveniles have black bills and smooth, black skin on their heads and necks. The Vulture’s short, square-tipped tail serves as a distinctive field mark. In flight, the toes of Black Vultures often extend beyond the tip of their tails. Unlike Turkey Vultures, Black Vultures hold their wings flat when soaring, rock less, and flap more frequently. In powered flight, Black Vultures intersperse short bursts of quick, shallow, stiff wingbeats with periods of gliding.

Breeding Habits

Black Vultures are monogamous and pairs are believed to mate for life. Pairs remain together year-round. Family members associate more closely with each other than with other individuals. Black Vultures nest in dark recesses usually under some type of cover. They do not build a nest, instead, they lay their eggs in rocky crevices, caves, tree cavities, hollow logs, and on the floors of abandoned buildings. Black Vultures perch for long periods in close proximity to potential nest sites as early as four to six weeks before egg-laying, presumably to determine if the site is free from disturbance. In many areas, safe nest sites are limited and pairs typically return to sites where they have previously been successful. Black Vultures perform aerial displays during courtship. At such times, males circle females with their necks extended, exhale loudly, and chase and dive towards them. Pairs also engage in the Up-Down Display, in which perched individuals spread their wings and alternately jump up into the air, while making a yapping sound. Black Vultures typically lay two eggs, which are incubated for 32 to 45 days. Both males and females incubate during alternating, 24-hour shifts. Adults sometimes position the eggs on top of their toes while incubating. After hatching, the young are brooded continually until 14 days of age. Thereafter they are brooded intermittently until they are 24 days old. Parents regurgitate food to their young, and small nestlings receive liquefied food as often as 20 times a day. When the young are 14 days old they begin to receive solid food. As the young mature, parents gradually spend more time away from the nest and feed older nestlings two to four times a day. Juvenile Black Vultures fledge at 10 to 14 weeks of age, but remain dependent on their parents much longer. Adults sometimes provide food for their young as long as eight months after fledging. Even once they have become independent, juveniles may continue to forage in social groups with their parents. Adults and juveniles often remain in close contact until the next breeding season, thereafter parents chase their offspring away from the nest site. After leaving their parents, juveniles enter a wandering stage during which they drift between roosts and follow adults to food sources while learning how to search for carcasses on their own.

Feeding Habits

Black Vultures are opportunistic aerial scavengers that feed on carrion of all types and sizes. Unlike Turkey Vultures, this species lacks a keen sense of smell and relies entirely on vision to locate food. While searching for food, Black Vultures typically fly at higher altitudes than Turkey Vultures and monitor the behavior of predators and other scavengers. They frequently follow successful Turkey Vultures to carcasses, and then aggressively chase them away. Great numbers of Black Vultures quickly gather at large food sources. While feeding, the species is aggressive and frequently chases off other scavengers including Turkey Vultures and crows. Black Vultures sometimes feed on the same carcass for several days. Carcasses of large mammals are the most common food sources. Individuals prefer to feed on fresh carcasses, but consume decaying meat as well. Occasionally Black Vultures capture live prey, most of which are young, weak, or sick small mammals or birds. The species also preys on eggs and nestlings, and, occasionally on newborn domestic animals. Individuals often feed at open-pit garbage dumps and piggeries. These Vultures also feed on vegetable matter including sweet potatoes, pumpkins, coconuts, and the fruit of oil palms.

Migration

Black Vultures are sedentary, except in northern portions of their range. In winter, particularly during harsh weather, many individuals leave the northernmost portions of their breeding range in the United States. Individuals sometimes undertake short-term local movements in advance of oncoming inclement weather and return once weather conditions improve. Most Black Vultures migrate in flocks that range in size from several individuals to several dozen birds. On migration, the species soars extensively both on thermals and mountain updrafts. Like other soaring migrants, Black Vultures typically avoid crossing large bodies of water. Black Vultures extended their range into Pennsylvania in the early part of the 20th Century, and the first confirmed account of nesting in the Commonwealth was reported in 1952. Since then, the Black Vulture has become a fairly common breeder near Hawk Mountain. The Sanctuary recorded its first migrating Black Vulture in the autumn of 1979. Local as well as migratory Black Vultures are observed at Hawk Mountain. Each autumn approximately 50 migrating Black Vultures are counted at the North Lookout, usually in October and November.

Conservation Status

The current world population of this New World species almost certainly exceeds several million birds. Most populations of Black Vultures appear to be healthy and stable. Their tolerance for, and close association with, humans has enabled it to increase in Central and South America in the last 400 years. Black Vultures benefit from human activities, including cattle-rearing, fishing, and garbage dumps, that provide increased or concentrated food resources. Black Vultures decline in areas where the available food supplies decrease as a result of increased sanitation measures. In the eastern United States the species’ range has expanded northward since the 1940s, and its numbers seem to be increasing overall. The factors responsible for range expansion are not well understood. Plausible explanations include the cessation of large-scale persecution, greater food availability, and recovery from declines which occurred in response to the widespread use of organochlorine pesticides, including DDT. Food resources are believed to have increased because of a greater availability of road kills, particularly deer. Black Vultures decreased in some parts of the United States during the DDT era of the 1940s to the early 1970s. When Black Vultures consume food containing DDT, the pesticide can accumulate in their fatty tissues, and eventually result in eggshell-thinning and reduced reproductive success. Although DDT no longer threatens vultures in the United States, the pesticide may continue to affect populations elsewhere. Environmental contaminants including mercury, lead, and insecticides can poison Black Vultures as well. Collisions with vehicles are another source of mortality. The loss of high-quality nest sites also affects the species. Forestry practices that reduce the number of tree cavities force Black Vultures to nest at sites where they are more susceptible to predation. Human disturbance may cause Black Vultures to abandon their nests, and pets sometimes predate eggs and nestlings. Even today, some Black Vultures are shot illegally. They also are inadvertently poisoned at carcasses baited for other scavengers, and are sometimes caught in steel leg-hold traps. Earlier in the 20th Century, persecution was a significant source of mortality for Black Vultures. Fortunately, large-scale persecution is no longer a threat to the species in the United States. Until the 1970s, Black Vultures were shot, caught in walk-in traps and subsequently killed, and poisoned by ranchers and farmers who were concerned about vultures spreading disease and attacking livestock.

| BLVU Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | ||

| 1974-2004 | 3.7 | 0.16 |

| 1980-1990 |

Black Vulture Reading List

BUCKLEY, N.J. 1999. Black Vulture (Coragyps atratus). No. 411 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

strong>FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. 2003. Raptors of eastern North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California