The Bald Eagle is the national symbol of the United States.

Haliaeetus leucocephalus

67-year annual average: 56

1992-2001: 118

Record year: 167 (1999)

Best chance to see: Early to mid-September

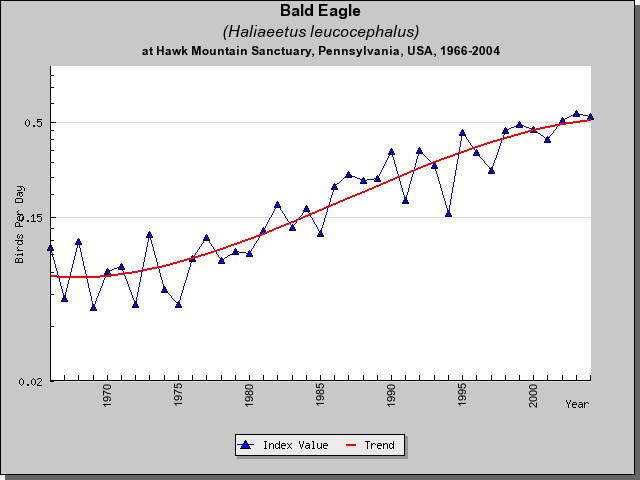

Longterm trends: Decreased during the pesticide era of the middle 20th Century; increasing since late 1970s. Reintroduced as a breeding species in Pennsylvania in the 1980s.

A.K.A.: American eagle, white-headed eagle, sea eagle

Field marks: Large, dark-bodied raptor, with broad, plank-like wings. Adults have a distinctive white head and tail, dark body, and dark wings. Immatures lack the white

head and tail, and often have white scattered throughout their dark body and wings.

Flight behavior: Migrates alone. Soars, glides, and, infrequently flaps while migrating.

Often migrates late in the day.

What size is a Bald Eagle?

- Wingspan6'-7'6"

- Length2'4"-3'2"

- W-L ratio2.6:1

- Weight6-14 lbs

Bald Eagle Raptor Bites

- Belong to the family Accipitridae, a group of 224 species of hawks, eagles, vultures, harriers, and kites.

- Found only in North America.

- One of 10 species of sea or fish-eagles characterized by the lack of

- feathers on their lower legs and feet.

- Were once called whiteheaded eagles.

- Adult Bald Eagles have a white head and tail with chocolate-brown body feathers.

- Juvenile Bald Eagles do not get their adult plumage until their fourth or fifth year.

- Often steal prey from other raptors, especially Ospreys (Pandion

haliaetus). - Are social outside of the breeding season, especially where food is

abundant. - Build some of the largest stick nests of any bird. Some of their nests are up to 8 feet across and weigh almost two tons.

- Are still threatened by shooting and trapping.

Seasonal Count - from North Lookout - 1934 to Date

Introduction

As the national symbol of the United States of America, the adult Bald Eagle is one of the best known and most readily identified birds in North America. With its chocolate brown body, white head and tail, large yellow beak, and wingspan of more than six feet, the adult eagle is unmistakable. The species’ range is restricted to North America from Alaska and Canada to Mexico. The Eagle is one of ten species of “fish or sea eagles” worldwide. Most Eagles prefer to live near aquatic habitats including reservoirs, lakes, rivers, and coastal areas, with significant forest cover close by. Bald Eagles are territorial during the breeding season. At other times of the year, however, they can be quite social, and winter aggregations are common in areas where food is abundant. More than a thousand eagles, for example, regularly congregate along the Chilkat River in Alaska where adult and juvenile Eagles feast on salmon that have died after spawning.

Despite being the national symbol of the United States, the Bald Eagle was extirpated from many parts of the country in the mid to late 1900s. At that time, Bald Eagles were still being shot in large numbers and many were being poisoned by pesticides. When Bald Eagles consume prey with pesticides present in their tissues, these chemicals can accumulate in the eagle’s fatty tissues and, over time, can kill the bird. Pesticides such as DDT affected eagles in another way as well: by interfering with their ability to produce strong eggshells for their eggs. A ban on the widespread use of DDT and other harmful pesticides, and decreased persecution due to increased education, allowed Bald Eagle populations to rebound in the 1980s and 1990s. Today, their populations continue to increase.

Identification

Bald Eagles typically exhibit a steady, deliberate flight pattern with slow wingbeats. In both soaring and gliding flight, the Eagle’s long, uniformly wide, plank-like wings are held straight out, at a right angle from the body. A very large head and bill are characteristic of the species and, in flight, the two extend beyond the body more than half the length of the tail. Eagles in adult plumage are easy to identify, with their white tail and head, yellow bill, and dark brown body. Immature eagles take about five years to acquire this characteristic plumage. During this time, individuals of the same age can exhibit substantial differences in appearance. In their first year, most individuals are dark brown with a dark beak, dark eyes, white axillary (armpit) patches, isolated white body and wing feathers, and whitish markings on the upperside of their tail. The underside of their tail is usually whitish with dark edges and a wide, dark terminal band. In their second year, most eagles have a whitish belly, a whitish triangle on their back, a wide, whitish line over their eyes, and a grayish beak. In their third year, the crown and throat are whitish in contrast to a dark eyeline, the beak is pale yellow, and the eyes are whitish or yellow. By their fourth year some Eagles resemble adults. Many, however, have whitish heads with a dark eye stripe, and some have white spots on their bodies and wings. A year later in their first adult plumage, a few individuals retain a trace of an eye stripe, and have some black on the tips of their tail feathers.

Breeding Habits

In areas where Eagles are sedentary, pair bonds usually remain intact throughout the year. Individuals often mate for life unless one member of the pair dies before the other. Bald Eagles generally are able to breed when they are five years old. In areas that have high densities of eagles, individuals may not breed until they are six or seven years old and in areas with low populations, individuals sometimes breed when they are four years old.

Most eagles nest in forested areas within two kilometers of open water. In areas where the shoreline has been developed, eagles sometimes nest farther inland. Nests are typically placed in the tallest trees in the immediate area. Most nest sites afford good visibility of the surrounding countryside. In areas lacking trees, eagles will nest on cliffs and on the ground. Ground nests usually have good flight access but limited predator access such as sites along prominent ridges, and on cliffs. Bald Eagle nests can be enormous. Many are used in successive years and some are more than eight feet across and weigh up to two tons. Although it is common for Bald Eagles to reuse their nests year after year, some pairs have two nests that they alternate between. Although nesting materials may be added sporadically throughout the year, during the breeding season, materials are often added on a daily basis. Serious nest building and maintenance usually begins one to three months before egg-laying. Both members of the pair help build the nest, with the female being responsible for arranging the sticks.

Eagles have one brood per year. Replacement clutches may be laid if the eggs are taken or destroyed early during incubation. Clutches range in size from one to three eggs. The female does most of the incubating, but the male also helps. Incubation begins when the first egg is laid. As a result, the eggs hatch asynchronously and the chicks differ in size and in their ability to compete for food.

Older chicks tend to get more food, and the last chick in a brood often starves except when food is abundant. During the first two to three weeks after hatching at least one parent typically remains at the nest. Females are at the nest for about 90% of this time, and males are there about half as often. Although both males and females hunt for their nestlings, males provide most of the food. Nestlings are unable to tear apart their food until they are about six weeks old. Adults spend less time at the nest as the nestlings mature. Chicks fledge when they are eight to fourteen weeks old. In the few weeks prior to leaving the nest, they exercise their wings by flying to perches near the nest.

Fledglings remain near their parents and siblings for an additional two to ten weeks before they disperse. During this fledgling period the young spend increasingly less time with the adults and begin to hunt on their own. Because Eagles first breed when they are about five years old, they have a long period to explore and move about before they find a mate and establish a territory. Local food availability and weather play important roles in determining the extent of their migratory movements during this sub-adult stage of their life.

Feeding Habits

Eagles typically search for food in aquatic habitats, and fish are their preferred prey. They are opportunistic hunters, however, and their diets vary considerably depending upon both season and location. In addition to fish, eagles feed on crustaceans, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Fish are primarily caught near the surface of the water, and Eagles often hunt near the shoreline. In the breeding season, at least, many eagles seem to prefer large fish. Most of the birds that Bald Eagles prey upon are medium-sized aquatic species including waterfowl. In some areas during the winter, ducks serve as an important food source. Although adept at catching prey, Bald Eagles readily act as scavengers, and they also steal food from other birds and mammals. Stealing is more common outside of the breeding season. Individuals are known to pirate food from other eagles, as well as from Ospreys and from other birds, and mammals. Carrion also is an important food resource, particularly in winter, when Eagles feed extensively on dead fish, birds, and mammals. Eagles will also congregate and feed at garbage dumps. Bald Eagles typically hunt from elevated perches or while flying over suitable habitat, but they also sometimes wade into water to catch prey. Bald Eagles even have been known to hunt cooperatively. Although most prey is consumed at a nearby perch, small prey sometimes is eaten in flight, and large food items are often fed upon at the kill site. Bald Eagles sometimes return to feed at a large carcass for several days.

Migration

The Bald Eagle is one of 26 North American raptors that are considered to be partial migrants.

Some Eagles remain on their breeding grounds year-round, and most migratory individuals are short- to moderate-distance travelers. Even so, a few individuals migrate up to 2200 km. Bald Eagles generally migrate alone, although they sometimes congregate at roosting and feeding sites during their movements. Like other raptors, individual Eagles begin their journeys as broad-frontal migrants, but thereafter many concentrate along leading lines. Bald Eagles from the northeastern United States and Canada follow the Appalachian Mountains or the Atlantic coast as they fly south in autumn. The species usually migrates throughout the warmest periods of the day. Thermal soaring serves as the chief migration strategy and the greatest numbers of migrants are seen between 1030-1700 hrs when thermals are strongest. Bald Eagles have a complex migration pattern that varies depending on food availability, the bird’s age, where it breeds, and the weather. Nesting Eagles are likely to stay on or close to their nesting grounds unless food supplies become scarce or weather conditions become intolerable. Individuals living in coastal areas in the northern United States and Canada often are sedentary, but individuals that live inland, in areas where most water freezes, generally leave their breeding grounds. Migrants winter primarily in coastal areas, but some eagles migrate inland as well. Young birds from northern areas usually migrate south earlier than older migrants, and young birds usually return to their eventual breeding grounds later than older migrants in spring. On their return migration, adults appear to be in a hurry to return to their breeding grounds, and overall, spring migration occurs across a shorter timespan than autumn migration. In the spring, adults feed to a limited extent, whereas younger birds are more likely to feed opportunistically and sometimes stop for extended periods at attractive food sources. In many southern locations, adult Eagles are often sedentary. Bald Eagles that breed in California, Arizona, and Florida exhibit an unusual migration pattern: young birds travel northward after they fledge and become independent of their parents. Bald Eagles in Florida begin nesting in November and December and their young sometimes fledge as early as late March. In spring and summer, young-of-the-year fly north to over-summering areas in the northern United States and southern Canada. They return to their birthplace in late summer early autumn. Older sub-adult eagles also move north, but usually not as far as first-year birds. Adult breeders seem to remain near their nests and only make local movements to areas where food is plentiful. A potential explanation for these northward movements by young Eagles is that these individuals travel to areas where there are greater opportunities to feed in less crowded areas. As a result of this unusual migration pattern, Hawk Mountain experiences two peaks in eagle migration each autumn. In late August-September, young individuals from southern populations are counted as they return to their Florida breeding grounds. In November-December a second peak occurs as individuals from breeding grounds north of the Sanctuary pass Hawk Mountain on their way to southerly wintering grounds. The severe population decline of Bald Eagles in the middle of the 20th Century was evident in migration counts at Hawk Mountain. In her book, Silent Spring, Rachel Carson used data from the Sanctuary to document the threat of pesticides at the time. Declines in the ratio of juvenile to adult Bald Eagles, which preceded the overall decline in eagle numbers, indicated that the population crash was due mainly to decreased reproductive success. By the 1970s, Hawk Mountain’s overall counts of Bald Eagles had dropped as low as 12 birds per autumn from an average of 56 in the 1930s and 1940s. Numbers of Bald Eagles counted at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary rose in the 1980s and 1990s, and increased numbers of Bald Eagles continue to be seen at Hawk Mountain. In the autumn of 2003, a record-breaking 216 Bald Eagles was counted at Hawk Mountain.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Conservation Status

There are currently more than 6,000 nesting pairs of Bald Eagles in the lower 48 United States. The world (North American) population is estimated at more than 100,000 birds. Once fledged, Bald Eagles have few natural enemies. Unfortunately, people remain the greatest source of mortality for Eagles. Human actions that directly threaten Bald Eagles include shooting, trapping, and poisoning. Indirect sources of mortality include environmental contaminants, collisions with buildings, bridges and power lines, ingestion of lead and plastic, and oil spills. Human development of critical shoreline habitat results in a loss of foraging, nesting, perching, and roosting sites. Habitat loss can hinder the expansion of breeding populations, and can limit or reduce the number of Bald Eagles in an area. Human threats to Eagles are not new. Native Americans killed Bald Eagles for ceremonial purposes and to collect their feathers. Following European settlement, eagles were killed to protect livestock and game species. In 1940, the Bald Eagle was listed as protected under the Bald Eagle Protection Act and it became illegal to kill, harass, or sell eagles and eagle parts, or to have eagles without permits in the lower 48 United States. Despite legal protection, persecution of Eagles continued. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s illegal shooting and the use of DDT led to precipitous declines and the extirpation of Bald Eagles from many areas. During this time, there were regional differences in the extent to which DDT affected eagle reproductive success. In Alaska, for example, eagle nesting success remained high at 70% and productivity averaged one young per nest. In the Great Lakes region, however, nest success dropped to 10%, and productivity fell to 0.1 young per nest. The southern subspecies of Bald Eagle (i.e. the one that breeds in the lower 48 United States) was listed under the 1966 Endangered Species Preservation Act, and in 1978 the entire species, including the population in Alaska, was listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Fortunately, the widespread use of DDT was banned in 1972 and eagle populations began to rebound. By 1995, the species was down-listed from Endangered to Threatened. By 1999 Eagle populations had reached many of the federal recovery goals, and many conservationists have suggested taking it off the Endangered Species List entirely.

Bald Eagle Reading List

Beans, B.E.1996. Eagle’s plume: preserving the life and habitat of America’s bald eagle. New York: Scribner.

Bent, A.C. 1937-1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey. (vol.1-2). New York: Dover.

Brauning, D.W. 1992. Atlas of breeding birds in Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Brown, L., & Amadon, D. 1968. Eagles, hawks and falcons of the world. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Dunne, P. 1995. The wind masters. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Gerrard, J.M., & Bortolotti, G.R. 1988. The bald eagle: haunts and habits of a wilderness monarch. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Johnsgard, P. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institute Press.

Stalmaster, M.V. 1987. The bald eagle. New York: University Books.

Field Identification

Clark, W.S., & Wheeler, B.K. 1987. A field guide to hawks of North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Clark, W.S. & Wheeler, B.K. 1995. A photographic guide to North American raptors. San Diego: Academic Press.

Dunne, P., Sibley, D., & Sutton, C. 1988. Hawks in flight. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Miscellaneous

BUEHLER, D.A. 2000. Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). No. 506 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

SNYDER, N. AND H. SNYDER. 1991. Raptors: North American birds of prey. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minnesota.

STOKES D.W. AND L.Q. 1989. A guide to bird behavior, volume III. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California.