Barn Owl

Tyto alba

Name

The genus name Tyto is Greek for “owl,” and the species name alba is Latin for “white.” Translation is thus “white owl.” The common name refers to this owl’s frequent use of barns and other man-made structures. This owl is also referred to as ghost owl, monkey-faced owl, and sweetheart owl.

General Description

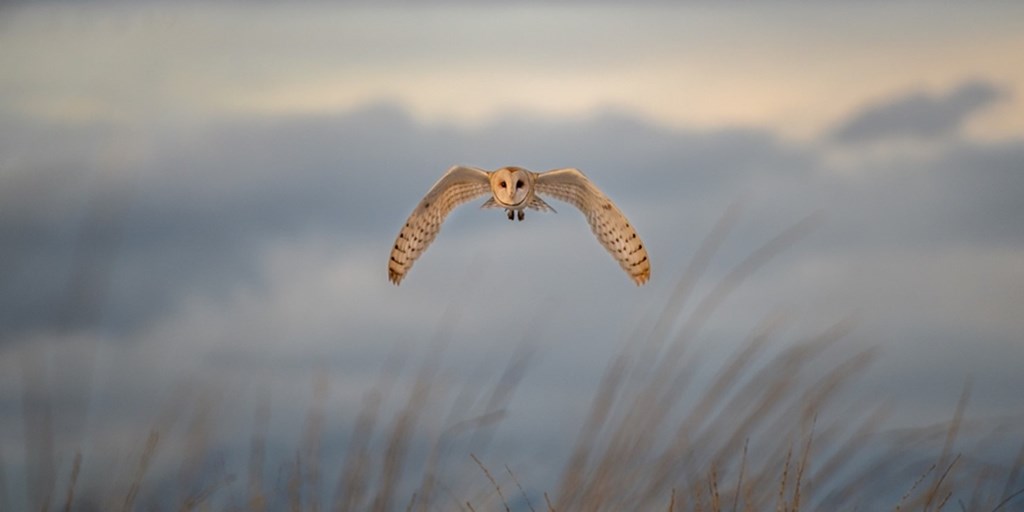

Barn owls are the only North American member of the genus Tytonidae, distinguished from the majority of other owl species by a multitude of traits, including a wishbone fused to the sternum, lack of ear tufts, long skull, defensive head-swaying, and small ear openings. They have relatively long legs in relation to their body size, a heart-shaped facial disk and dark penetrating eyes. Their breast and head are white with golden-cinnamon tinge and dark flecks. Their back is a slate gray, interspersed with cinnamon and small white flecks. Females have heavier markings and a darker facial disk on average than males. Juveniles undergo two layers of down feathers during the nestling stage rather than one stage, as opposed to owls from the Genus Strigidae, which only have one down layer.

Similar species: short-eared owls and barn owls can be confused in flight given their buoyant flap, though short-eared owls have dark primary tips to their feathers and dark wrist patches on the underwing. Barn owls have neither of these field marks.

Fun Facts

• Barn owls can eat more than 3,000 rodents over the course of one breeding season, and one study in Israel found that when barn owls nested near alfalfa fields, crop yield increased by $30/hectare (2.47 acres) as a result of predation on voles.

• Female barn owls have more spots on their chest than males; this may be used as a signal of good health, since during experiments females with more spots have attracted fewer parasitic flies and subsequently receive higher levels of attention from their mates.

• Barn owls have better quality hearing than any other animal that has thus far been tested.

• Barn owls have one of the lowest wing-loading ratios of any North American owl, meaning they have broad wings in relation to their overall body mass. This allows them to fly slowly and buoyantly over open habitats in search of food.

• Banding records have revealed an average lifespan of only 1.8 years for barn owls, most likely influenced by low juvenile survival.

• Barn owls live on every continent except Antarctica, making them the most widespread owl species in the world.

• Barn owls have been found nesting in drive-in movies screens.

Size

| Females | Males | |

| Wingspan | 84-106 cm (33-42 in.) ✏️✏️✏️✏️✏️ (5 pencils end to end) | Same |

| Mass | 567 g (1.25 lbs) 🍋🍋🍋🍋🍋 5 lemons | 474 g (1 lbs) 🍋🍋🍋🍋 4 lemons |

Vocals

Eighteen different calls have been described for the barn owl, falling into several categories: territorial, defense, social contact, nestling calls, and begging and feeding. Many of these vocalizations are variations of screams, hisses, or “purring.” Screams and screeches are most often made in territorial and defensive circumstances, and more often by the male. Purring calls are given during social interactions such as a female begging a male for food, or a male inviting his mate to assess a nest site. Hissing is used to communicate mate recognition, distress, hunger, and sexual excitement.

When threatened, barn owls utilize an effectively frightening display in which they lower their “chin” to the ground and slide it back and forth, hissing, snapping their beak, and raising their wings in a hunched form above their heads.

Habitat

Barn owls are open habitat specialists, though in their context the definition of open space is broad. Sites with a combination of grassland, wetland, agricultural land, and riparian areas are especially desirable for barn owls. They seek roosting and nesting sites in man-made structures, including but not limited to barns, bridges, baseball stadiums, military bunkers, silos, and even abandoned cars. Natural sites such as cliffs, tree cavities, and caves also provide shelter for barn owls, however these sites were relied upon more heavily prior to human expansion.

Feeding

Barn owls are rodent specialists. Regardless of where they live, mammals compose roughly 90% of their diet, though exact species composition varies greatly depending on what’s available. Generally, barn owls take whichever small mammals are easiest to kill. For example, Pennsylvanian barn owls take mostly meadow voles, while Louisiana owls consume a high proportion of cotton rats, and Grecian owls feed primarily on the Western European house mouse. If small mammal numbers are scarce, alternative prey will be consumed such as bats, sparrows, European starlings, amphibians, earthworms, and moles. Barn owls are thus specialists, except when they’re not.

Barn owls hunt at dawn and dusk, but mostly at night. They will repeatedly use successful hunting routes as long as the wind allows, and they likely time their outings carefully so that their main predator, the great-horned owl, does not cross their path. Barn owls rely heavily on their remarkable hearing to catch prey, made possible by uniquely placed asymmetrical ears; the left ear is slightly higher than the right. This anatomical feature greatly enhances the ability of a barn owl to pinpoint the location of their prey.

Nesting

Barn owl courtship begins early in the breeding season, though the male’s displays do not always precede copulation which may begin even earlier. Males begin their courtship by engaging in territorial flights during which they emit screeches and hunt for rodent gifts to present to their mate. Males may perform a “moth flight,” for the female during which he hovers in front of her with his feet dangling and his white underparts exposed, or perhaps the “in-and-out flight” which entails him flying back and forth from the nesting site, enticing her to follow. The male may also clap his wings during display flights. If interested, the female will respond with “snore” calls to elicit presentation of food and subsequent copulation.

Barn owls are cavity nesters, using an assortment of shelters as mentioned in the habitat description. They have a longer potential breeding season than many other North American owls, and while March through June is the average window, barn owls may breed at other times of year. For example, in 2019 a barn owl nest with 5 young was discovered in October near State College, PA, though only 3 of the 5 survived.

Clutch size varies from 2 to 11 eggs, though overall fledging success has been observed to decrease with 5 or more eggs in the nest unless there is an associated prey boom that year. Incubation lasts for 29-34 days, and fledging occurs around 50-64 days of age.

As Scott Weidensaul said in his book on North American owls, “barn owls mature fast, breed hard, and die young.” Because their life processes are concentrated into a short period of time, they have developed methods of maximizing productivity when resources allow by having a flexible clutch size, employing double-clutching (laying a replacement clutch if the first fails), and breeding when the time is right.

Migration

Barn owl movements are poorly understood. There is some evidence of autumn migration, though this is unconfirmed. Juveniles disperse after fledging, some traveling as far as 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) from their nest, while most others remain within 20 kilometers (12.5 miles) from their nest. Some large-scale movements of juveniles have been observed in specific years, potentially linked to a decrease in rodent availability and a consequential dispersion in search of food.

Current Conservation Status

The barn owl is listed as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the state of Pennsylvania, though IUCN has them ranked as a Species of Least Concern globally. Loss of habitat is the primary threat to this species locally; they require grasslands and/or agricultural land that hosts a diversity of vegetation rather than monoculture croplands. Monoculture is the cultivation of one crop on the same land, year after year, a practice that causes the soil to stagnate and stunts biodiversity. The number of different plants in an ecosystem is directly related to the number of species that can be found there, and while barn owls are rodent specialists, they still rely upon a healthy and biodiverse food web to ensure that they will have enough sustenance for themselves and their offspring.

Another threat to barn owls is vehicle collisions. In a shocking study conducted in Idaho, researchers found an average rate of one dead barn owl per kilometer (every 1.6 miles) of road. Barn owls are especially susceptible to vehicle collisions since they hunt at the same level above the road as cars are tall, and because hunting is especially productive at roadside edges. The reasons for this are multifaceted; roadside edges typically contain heat from asphalt conductivity and fertilizer runoff, as well as ample water runoff. They also host high plant diversity since human cultivation strategies such as monoculture are not feasible close to the road. This combination of factors results in high rodent numbers, which attract predators such as red-tailed hawks, kestrels, and barn owls.

Like all raptors, barn owls are valuable ecosystem bioindicators, which means they offer us a bar with which to measure the health of the environment. If barn owls are thriving, there must therefore be a healthy ecosystem supporting them. It’s all connected, and barn owls are a part of the web.

How can you help barn owls?

If you are a landowner, you can help barn owls by welcoming them as pest managers. This means that instead of relying on rodenticides, which are extremely harmful to raptors including barn owls, you and your community can support habitat features that attract barn owls, and through these actions, increase the rodent control on your land. Installing barn owl nest boxes, encouraging rotating crop cycles, creating edge habits, halting the use of rodenticides, supporting barn owl research, and reporting sightings link to sightings form here are just some of the potent ways you can help these beautiful birds. There are also cash incentives for landowners that support wildlife improvement areas through a project called the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP).

To learn more about these potential actions click here and/or contact Dr. Laurie Goodrich, the Sarkis Acopian Director of Conservation Science at Hawk Mountain: [email protected].

For specific questions related to installing nest boxes, or to support research on barn owls, contact Dr. JF Therrien, our Senior Scientist at [email protected].

For information on Hawk Mountain’s Farmland Raptor Project, aimed at ensuring that barn owls and other grassland raptor species will continue to grace surrounding landscapes, click here.

If you are not a landowner, you can still help barn owls by spreading the word, supporting research, reporting sightings, and encouraging your community to protect and cultivate tracts of healthy open habitat.

Special thanks to Traci Sepkovic and Clinton Mcdonald for their generous photo contributions to this account.

Information written and compiled by Zoey Greenberg.

Sources

Boves, Than & Belthoff, James. (2012). Roadway mortality of barn owls in Idaho, USA. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 76. 1381-1392. 10.2307/23251436.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2019). All About Birds: Short-eared Owl. Retrieved from

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Short-eared_Owl/maps-range

Johnsgard, P. A. (1988). North American owls: biology and natural history. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian

Institution Press.

Weidensaul, Scott. (2015). Owls of North America and the Carribean. New York: NY.: Peterson Field Guides.