American Kestrels are the smallest and most colorful falcons in North America.

Falco sparverius

67-year annual average: 389 (1992-2001: 611)

Record year: 839 (1989)

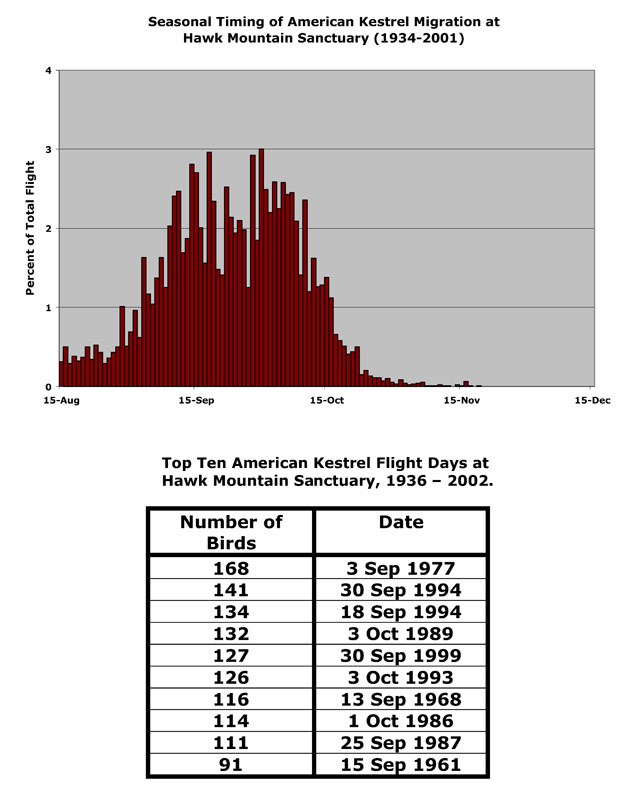

Best chance to see: Late September, when daily chance is 78%, and passage rate is 1 bird/hour.

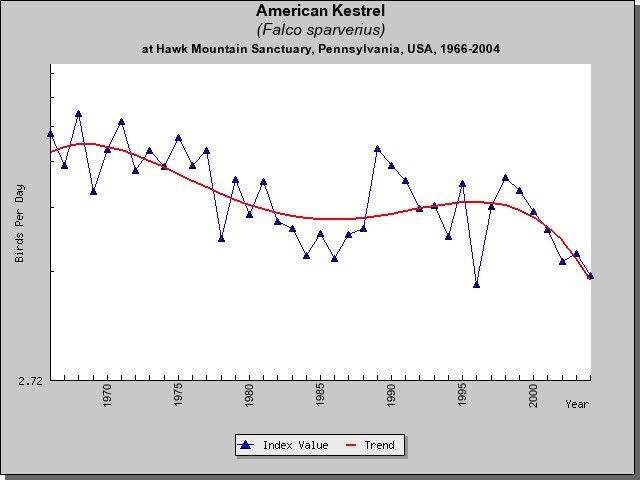

Longterm trends: Increased from 1930s through mid-1970s, decreased in late 1970s and early 1980s, relatively stable in late 1980s and early 1990s.

A.K.A.: Sparrow hawk, killy hawk, mouser

Field marks: blue-jay-sized, colorful falcon, with long, sickle-shaped wings, a longish tail, and conspicuous head markings. Male American kestrels have rufous to white underparts, (sometimes with black spots); blue wings, rufous backs, and rufous tails with black tips. Females have streaked, creamy underparts, with rufous barred backs, wings and tails.

Flight behavior: Typically migrates alone, although sometimes travels in small flocks with other raptors. Occasionally soars; usually flaps and glides while migrating. Quick, erratic flight.

What size is an American kestrel?

- 1'8"-2'Wingspan

- 8-11"Length

- 2.2 : 1W-L Ratio

- 3.5-5Weight (in ounces)

American Kestrel Raptor Bites

- Belong to the family Falconidae, a group of 60 species of caracaras, falconets, pygmy falcons, forest falcons, and falcons.

- Are about the size of a Blue Jay.

- Were once called sparrow hawks.

- Occur from Tierra del Fuego in southern South America, to the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada.

- Occur only in the New World.

- Because of their small size and habit of perching on utility lines, American Kestrels are often mistaken for Mourning Doves.

- Male American Kestrels have blue-gray wings; females have brown wings.

- Male and female American Kestrels can be told apart by their plumage as early as three weeks of age.

- Do not build their own nests, but instead nest in cavities made by other birds, and in nestboxes built by humans.

- Some Kestrels migrate long distances while others do not migrate at all.

- In North America, male Kestrels winter farther north than do female kestrels.

- In winter, female Kestrels hunt in more open, less wooded areas, than do

males. - Hawk Mountain Sanctuary has been erecting nestboxes for Kestrels in the Kempton Valley since the early 1950s.

- An American kestrel is the smallest and most colorful falcon in North America and is one of the best known, most frequently observed, and readily identifiable raptors in North America. Kestrels are conspicuous, colorful, open-habitat birds of prey about the size of a Mourning Dove.

Where do American kestrels live?

The American kestrel occurs throughout the Western Hemisphere from Alaska and Canada to southernmost South America. They are the smallest and most widespread falcons in North America. Kestrels can be found in most open habitats with adequate cavities for nesting and perches for hunting. The species readily adapts to human-modified environments, and is frequently seen in pastures and parklands perched along the road. Historically, Kestrels have benefited from agricultural development. However, recent habitat changes including urbanization, suburbanization, and reforestation have the potential to reduce the amount of available habitat for the species. Identification Like other falcons, Kestrels have long, pointed wings and long tails.

Compared with its larger cousins the Merlin and Peregrine Falcon, the Kestrel has less powerful wingbeats, and appears more buoyant in flight. Unlike many other raptors, Kestrels exhibit sexually dimorphic plumage. A unique characteristic of the Kestrel is that individuals acquire adult, sexually dimorphic plumage even before they fledge. Kestrels have reddish-brown backs and tails, blue-gray crowns with variable amounts of rufous, and two dark vertical stripes on the sides of their heads.

They have two dark “eyespots” on the back of their head. Male Kestrels have blue-gray wings. Females have reddish-brown wings with black barring. Males have rufous tails with one wide, black sub-terminal band and a white tip. Females have rufous tails and many black bars. The light-colored underparts of females typically are heavily streaked with brown; those of males have variable amounts of dark spotting or streaking. Females are about 10-15% larger than males.

When do American kestrels nest?

American Kestrels are secondary cavity nesters that nest in existing natural and man-made cavities. The species prefers nest sites that are surrounded by suitable hunting grounds and that have unobstructed entrances. In some areas, the lack of available nest cavities limits the number of breeding pairs. Kestrels often use cavities excavated by woodpeckers. Crevices in rocks and cavities in stream cut banks function as potential nest sites as well.

Will American kestrels use a nestbox?

Kestrels also nest in buildings and other man-made structures including nest boxes erected for the species. Nest-box programs for kestrels allow populations to grow in areas where nest sites are limiting.

When do American kestrels breed?

American Kestrels exhibit territory fidelity and many nest in the same territory year after year. Pairs reuse nest sites particularly if they have successfully raised a brood there previously. Kestrels typically are monogamous and some pairs remain together across years. In sedentary populations, kestrels often remain at the nest site for the entire year. In migratory populations, males return to the breeding grounds first and when females arrive they associate with territorial males. Pairs bond using aerial displays and courtship feeding. Aerial displays incorporate a series of sequential dives and ascents, during which the male calls several times. Males play the primary role in searching for suitable nest sites. After finding a potential nest site, the male seeks out the female and leads her to it. In some cases the male carries food, “flutter-glides,” (i.e. flies with short, quick wingbeats in slow, buoyant flight) and calls to entice the female to follow him to a nest site. American Kestrels are fairly vocal during the breeding season. Their most common call is a rapid, high-pitched klee-klee-klee-klee. The male often “flutter-glides” and calls as he approaches the nest site when delivering prey. When he does, the female flies out of the nest cavity and “flutter-glides” with him. Both fly together to a perch and the male transfers food to the female. Males do most of the hunting until the young are two weeks old, thereafter both male and female supply food to their young. Females often create a depression or “scrape” in the substrate on the floor of the cavity in which to lay their eggs. Pairs usually raise a single brood each year, but kestrels lay replacement clutches if the first clutch is lost early in the season. On rare occasions pairs raise two broods in a single season. American Kestrels usually lay four to five eggs, and incubation begins shortly before the last egg is laid. The youngest chick often is unable to compete for food with its dominant, older siblings and sometimes does not survive if food is scarce. Incubation takes about 30 days, and the female does most of it. After the eggs hatch, the female broods the nestlings continually until they are about nine days old. Thereafter, she broods only at night and during periods of inclement weather. As her brooding time decreases, her time spent hunting and her role in food provisioning increases. When the nestlings are two weeks old, the adults begin to leave intact prey at the nest. Fledging occurs about 30 days after they hatch, often over a period of several days. Young kestrels depend on their parents for food for two to three weeks after they fledge. During this time, the young sometimes return to the nest cavity to roost, and remain close to their siblings.

Feeding Habits

American Kestrels are opportunistic hunters that forage in open areas with short vegetation. The species is primarily a “sit-and-wait” perch-hunter, and elevated perches that afford good visibility of the surrounding area are an important component of suitable habitats. Hovering flight is a conspicuous, yet less frequently used hunting method. Kestrels typically hover-hunt where perches are lacking, usually in moderate winds and updrafts. Although most prey items are caught on the ground, insects and birds sometimes are taken in flight. Kestrels catch their prey with their feet and thereafter administer a killing bite to the back of the head.

Small prey items sometimes are eaten on the ground or in flight, but larger items usually are brought to a perch. Caching of surplus food occurs throughout the year, but the frequency of this behavior tends to be highest in autumn and winter and lowest in summer. The species preys mainly on insects and small mammals. Diets vary geographically and seasonally. American Kestrels are more proficient at capturing insects than other prey types. Kestrels usually consume small insects whole, but sometimes only eat the head and internal parts of larger insects. Commonly taken insects include grasshoppers, cicadas, beetles, dragonflies, butterflies and moths. Spiders and scorpions are eaten as well. American Kestrels also take small rodents including voles, mice, and shrews, as well as small birds, reptiles, and amphibians. The species rarely feeds on carrion except for prey that it has previously killed and cached.

Do American kestrels migrate?

The American Kestrel is one of 26 North American raptors that are partial migrants.

Some, but not all, populations of kestrels are migratory. American Kestrels breeding in northern portions of their range are more migratory than those breeding farther south, and birds in northern areas migrate farther than those in southern areas. Many southern populations are sedentary. The species exhibits a “leap-frog” pattern of migration in which northern birds winter south of southern birds. In comparison to Merlins and Peregrines, which often fly to the tropics to overwinter, most American Kestrels breeding in North America overwinter in the United States. Like many other raptors, migrating American Kestrels concentrate along leading lines while migrating, particularly along the Atlantic Coast, the shorelines of the Great Lakes, and the ridges of Appalachian Mountains in the East and the Rocky Mountains in the West. In general, migration counts of American Kestrels are higher at coastal watch sites than at inland watch sites. Kestrels, like other falcons, are chiefly self-powered migrants that only occasionally soar on migration. Even so, American Kestrels often capitalize on favorable soaring conditions, such as mountain updrafts and thermals, while traveling. The species avoids large water-crossings. At Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, kestrel flights are greatest on days when a cold front has passed through the area, presumably because of the strong updrafts that occur at such times. In autumn, juvenile and female kestrels tend to migrate earlier than do adult males probably because males take longer to complete their pre-migratory molt than do females. At Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, the median date of female passage precedes that of males by 11 days. Late arrival on the wintering grounds may force males to spend the winter in sub-optimal habitat if more favorable habitats already are occupied. In southern North America, sexes appear to winter in different habitats with females occurring in more open habitats and males occurring in more wooded areas. At Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, kestrel migration peaks in mid-September through mid-October.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Conservation Status

The current population of this New World species is believed to exceed four million birds. By the end of the 20th Century, American Kestrel populations were decreasing in parts of the northeastern United States, as well as Texas and Arkansas. Although kestrels are well-adapted to human-dominated environments, measures that decrease the amount of foraging habitat and the number of nest sites, such as changes in farming practices, loss of agricultural areas, and increased suburbanization and urbanization negatively impact them. American Kestrels suffer from competition with other species for nest sites as well. European Starlings, Screech Owls, Northern Flickers and squirrels are prospective nest competitors. In some areas, provision of artificial nest boxes enables kestrels to increase in number and allows populations to expand into formerly unused locations. Recent increases in the numbers of Sharp-shinned Hawks and, in particular, Cooper’s Hawks, two species that prey on kestrels, appear to be linked to at least some of the declines in the Northeast. Although persecution still occurs, shooting incidents are uncommon. Historically, American Kestrels were shot on migration. Collisions with vehicles, buildings and wires, attacks by cats and dogs, and electrocution are additional sources of mortality. Poisoning remains a threat locally, but no source of widespread contamination is apparent. Insecticides, which can kill kestrels outright, also can affect their populations by decreasing the amount of their available prey. American Kestrels have been used as an experiment model for other species of raptors in toxicological studies, including studies of the effects of DDT on eggshell thickness. The species also has been used in studies that examined the effects of electric and magnetic fields on birds.

| AMKE Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | -3.8 | 0 |

| 1974-2004 | -1.6 | 0 |

| 1980-1990 | -0.2 | 0.78 |

American Kestrel Reading List

ARDIA, D.R. AND K.L. BILDSTEIN. 1997. Sex-related differences in habitat selection in wintering American kestrels, Falco sparverius. Animal Behaviour 53:13051311.

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

SMALLWOOD, J.A. AND D.M. BIRD. 2002. American Kestrel (Falco sparverius). No. 602 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

STOKES, D.W. 1979. A guide to bird behavior, volume I. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. 2003. Raptors of eastern North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California

Bent, A.C. 1937-1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey. (vol.1-2). New

York: Dover.

Brauning, D.W. 1992. Atlas of breeding birds in Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh: University

of Pittsburgh Press.

Brown, L., & Amadon, D. 1968. Eagles, hawks and falcons of the world. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Cade, T. 1982. Falcons of the world. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Craighead, J.J., & Craighead, F., Jr. 1969. Hawks, owls and wildlife. New York: Dover.

Dunne, P. 1995. The wind masters. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary Association. 1997. Nestboxes for kestrels. Kempton, PA: Hawk Mountain Sanctuary Association.

Johnsgard, P. 1990. Hawks, eagles and falcons of North America. Washington DC:

Smithsonian Institute Press.

Field Identification

Clark, W.S., & Wheeler, B.K. 1987. A field guide to hawks of North America. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin.

Clark, W.S. & Wheeler, B.K. 1995. A photographic guide to North American

raptors. San Diego: Academic Press.

Dunne, P., Sibley, D., & Sutton, C. 1988. Hawks in flight. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.