Northern Goshawks are revered in many cultures as a symbol of strength.

Accipiter gentilis

67-year annual average: 71

1992-2001: 78

Record year: 347 (1972)

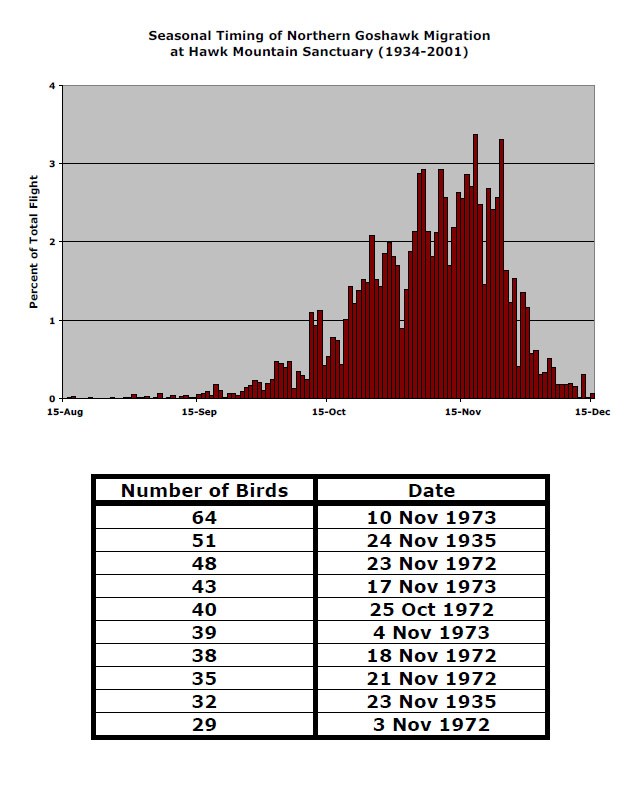

Best chance to see: Mid- to late November.

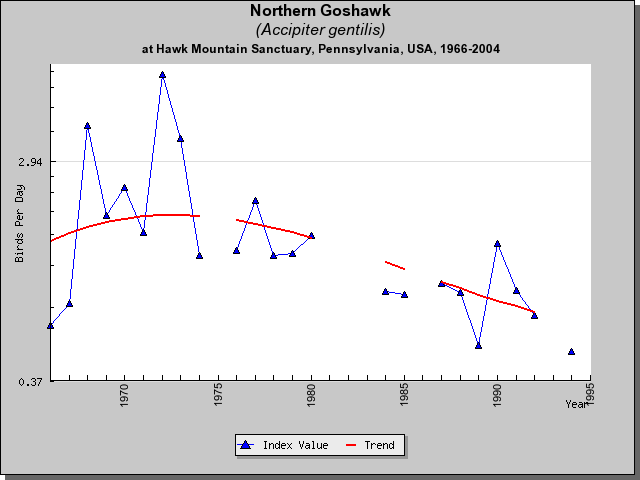

Longterm trends: Difficult to discern in this irruptive migrant. Counts In 1980s and 1990s not as high as during early 1970s.

A.K.A. Gos, Goshawk, Blue Darter

Field marks: Robust, redtail-sized accipiter, with rounded wings, and long rudder-like, wedge-tipped tail. Juveniles are brown above and light underneath with heavy, dark streaking. Adults are grayish above and whitish below. An oversized, more robust version of the Cooper’s Hawk, broader wings and a wider tail.

Flight behavior: Solitary migrant. Soars, but frequently flaps and glides while migrating. An irruptive and invasive migrant, usually at 10-year intervals when grouse and snowshoe hare populations crash in Canada’s boreal forests. At such times, males precede females on migration, and juveniles precede adults. The three most recent invasions at Hawk Mountain occurred in 1972-1973, 1981-1983, and, possibly, 1993 and 1995.

What Size is a Northern Goshawk?

- Wingspan2'10"-3'8"

- Length18"-24"

- W-L ratio2:1

- Weight1.5-2.6 lbs

Raptor Bites

- Northern Goshawks belong to the family Accipitridae, a group of species of hawks, eagles, vultures, harriers, and kites.

- Are the largest and least sexually dimorphic accipiters in North America.

- Northern Goshawks, the most widely distributed of all accipiters, are found in Europe, Asia, Japan, and Northern Africa, as well as in North America.

- Are revered in many cultures as a symbol of strength.

- The image of a Northern Goshawk adorned the helmet of Attila the Hun.

- Because it feeds on grouse, ducks, rabbits, and hares, the Northern Goshawk was once called “the cook’s hawk.”

- Are ferocious defenders of their nests.

- Feed on many other raptors, including Merlins (Falco columbarius) and American Kestrels (Falco sparverius).

- Although southern populations of Northern Goshawks are largely sedentary, northern populations are irruptive migrants that invade the United States when prey populations plummet in Canada.

- Are often used in falconry.

- Earlier this century, The Pennsylvania Game Commission had a five-dollar bounty on Northern Goshawks.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

The Northern Goshawk is the most widely distributed Accipiter in the world. A denizen of mature forested regions, the species inhabits boreal and temperate forests in North America, Europe, northwestern Africa, continental Asia, and Japan. In North America, goshawks occur in Canada, the northern United States (including much of Alaska), the mountainous western United States, and northwestern Mexico. The largest of the three North American Accipiters, Northern Goshawks are powerful raptors about the size of Red-tailed Hawks.

Historically, Goshawks have been prized falconry birds admired for their capacity to take large prey. In 1929, a five-dollar bounty was placed on the goshawk by Pennsylvania Game & Fish in an effort to protect game species that were sometimes preyed upon by goshawks. The bounty greatly increased raptor shooting throughout Pennsylvania, including along the Kittatinny Ridge. Accounts of irruptions of goshawks in the late 1920s, together with raptor shooting at Hawk Mountain, attracted the attention of conservationists, and ultimately led to the founding of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, the world’s first sanctuary for birds of prey. Goshawks and other North American Accipiters, or “bird-hawks” were among the last raptors to receive legal protection, and it was not until 1972 that all raptors were protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Identification

Adult goshawks have black crowns, white eyebrows, and red irises. As adults, Northern Goshawks are gray above and light gray with black horizontal bars and vertical streaks below. Their tails have a series of alternating dark-gray and light-gray bands. Females typically are larger, browner, and have more heavily marked underparts. Juveniles have brown heads, orange irises, and less distinct, whitish eyebrows. From above, juveniles are brown with a fair amount of white mottling. From below, their cream-colored underparts are heavily streaked with brown. The tails of juveniles have a series of wavy, alternating dark-brown and light-brown bands with thin white borders.

Like other Accipiters, the goshawk’s typical flight pattern consists of a series of quick wingbeats interspersed with brief bouts of gliding. Compared to the two smaller North American Accipiters, the flight of Northern Goshawks is more direct, and the flapping is slower with deeper wingbeats.

Breeding Habits

Goshawks nest in mature deciduous, mixed-deciduous, and evergreen forests with large trees, open understories, and sparse ground cover. Goshawks usually select the largest trees in an area for nesting, and most nests are placed on a horizontal branch, either in a fork or near the trunk. Nests are constructed of sticks and lined with bark chips, and are up to 91 cm across. Pairs typically maintain one to eight alternate nests in their territory. Although goshawks sometimes use the same nest in successive years, they are more likely to use alternate nests.

Prior to and during nest building, one or both birds perform aerial displays to advertise their territory. Nest construction begins at the start of courtship. Females do most of the nest building and generally display more frequently than males. Goshawks are usually silent except when they are courting. While displaying, individuals often call and spread their undertail coverts. Goshawks perform “sky dances,” which involve “high-circling” followed by “slow-flapping” and “undulating flights.” Throughout the course of the “sky dance,” birds lose altitude, and at the end of the display individuals either “high-circle” or dive into the forest. In addition to “sky dancing,” Northern Goshawks also perform the components of the “sky dance” alone. Males sometimes pursue females. With the female generally in the lead and the male following closely behind, the pair typically flies with slow, deep wingbeats and glides with their wings held in a steep dihedral or “V.”

Northern Goshawks are monogamous, and pairs typically lay a single clutch of three to four eggs each year. The incubation period lasts 35 to 38 days and the female does most of the incubating. For nine to fourteen days after the eggs hatch, the female remains at the nest brooding the nestlings. Thereafter, females spend less time brooding during the day, but continue to brood at night until the nestlings are 24 days old, after which they are brooded only during periods of wet and cold weather. Young goshawks fledge when they are 36 to 42 days old, and they become independent four to eight weeks later. Males fledge earlier and become independent sooner than their female siblings. Fledglings remain dependent on their parents and continue to associate with each other while their flight feathers harden and they learn how to hunt. As they become more proficient in flight, fledglings fly toward and intercept their parents as the latter return with prey.

Feeding Habits

Northern Goshawks hunt in both forested and open habitats. Like other Accipiters, goshawks have short, powerful wings and long tails, which together provide maneuverability and quick bursts of speed. Goshawks are primarily a short duration, sit-and-wait hunter, and they typically travel through the forest in a series of short flights that are interspersed with brief periods of perch hunting. The species also hunts on the wing from fast-searching flights. To surprise their prey, goshawks fly along forest edges, and through dense vegetation. They are both aggressive and persistent hunters and in some instances, pursue escaping prey on foot. When breeding, goshawks cache food in order to maintain a ready supply for their young, especially when the nestlings are small and require frequent, small feedings. Cached prey items usually are placed on a branch near the trunk or are wedged between branches.

Goshawks are opportunistic predators whose diets vary considerably depending upon prey availability. In North America, goshawks prey upon many species of birds and mammals, primarily feeding on ground squirrels and tree squirrels, rabbits, hares, large songbirds, and small- to medium-sized gamebirds. Goshawks also take reptiles and insects. Historically the Passenger Pigeon was a frequently taken prey item. In northern parts of its range, the Northern Goshawk depends on Snowshoe Hares and, to a lesser extent, Ruffed Grouse. The cyclic nature of these species affects goshawk movements, and individuals are more likely to migrate in years when populations of these prey species crash. Birds usually are caught by goshawks on the ground, but some are taken in flight as well. Avian prey are plucked prior to being eaten, and goshawks typically have a traditional plucking post within their territory.

Migration

The Goshawk is an irruptive migrant. Whereas some goshawk populations in northern areas are believed to migrate regularly, southern populations tend to be sedentary. In some areas, Northern Goshawks feed upon Snowshoe Hares, and the population cycles of hares affects goshawk migration behavior, with more goshawks migrating when hare populations crash. In the eastern United States, Snowshoe Hare cycles and subsequent goshawk irruptions have been observed since the late 1800s and historically “irruptions” of goshawks occurred once a decade. The most recent large-scale irruption of goshawks in the East, however, occurred during the autumn seasons of 1972 and 1973 following a severe crash in hare populations across much of Alaska and Canada. Since the early 1970s eastern hare populations have experienced partial population cycles and have not crashed, which may explain the lack of irruptions of goshawks since then.

In most years, at least some juveniles leave the breeding grounds in autumn, and during irruption years juveniles are more migratory than adults. Juveniles typically depart earlier than adults, and within age classes males generally precede females on migration. Northern Goshawks usually migrate alone, and are solitary and nomadic in winter.

Like other raptors, Northern Goshawks often follow leading lines on migration. Concentrations of goshawks are observed along mountain ridges, shorelines, and coastlines. In eastern North America, birds migrate along the northern shores of the Great Lakes and south along the Appalachian Mountains and the Atlantic Coast. In North America, the largest flights are seen at Hawk Ridge, Minnesota at the western edge of Lake Superior. Although goshawks in the West may migrate across a broad front, significant numbers concentrate along the Rocky Mountains. At Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, and presumably elsewhere, the largest numbers of goshawks are seen during the several days after the passage of strong cold fronts.

The goshawk flight is relatively protracted at Hawk Mountain, with migration from late September through early December, and a peak in late November. An average of 70 Northern Goshawks are counted at Hawk Mountain each autumn.

Conservation Status

The current world population of Northern Goshawks likely exceeds one million birds.

Northern Goshawks have few natural predators. In North America, Great Horned Owls kill both adult and juvenile goshawks. Overall, the species suffers most from habitat loss and illegal persecution. Today incidents of direct persecution are infrequent in North America, however shooting, trapping, and poisoning remain problematic in Europe.

Currently, the species appears to be stable in the United States, and goshawks are reoccupying portions of their former range where reforestation has occurred. Because the species is secretive during the breeding season and is an irruptive migrant, assessing their numbers is challenging.

Northern Goshawk Reading List

Bent, A.C. 1937-1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey. (vol.1-2). New

York: Dover.

Brauning, D.W. 1992. Atlas of breeding birds in Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh: University of

Pittsburgh Press.

Brown, L., & Amadon, D. 1968. Eagles, hawks and falcons of the world. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Craighead, J.J., & Craighead, F., Jr. 1969. Hawks, owls and wildlife. New York:

Dover.

Dunne, P. 1995. The wind masters. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Johnsgard, P. 1990. Hawks, eagles and falcons of North America. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institute Press.

Squires, J.R., & Reynolds, R.T. 1997. Northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis). In The Birds of North America, No. 298 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences, and Washington DC: The American Ornithologists’ Union.

White, T.H. 1979. The goshawk. New York: Lyons & Buford.

Field Identification

Clark, W.S., & Wheeler, B.K. 1987. A field guide to hawks of North America.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Clark, W.S. & Wheeler, B.K. 1995. A photographic guide to North American

raptors. San Diego: Academic Press.

Dunne, P., Sibley, D., Sutton& , C. 1988. Hawks in flight. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.