Northern Saw-whet Owl

Aegolius acadicus

Name

Common name “Saw-whet” refers to the parallel between this owl’s vocalizations and the sound produced when whetting, or sharpening a saw blade. Latin genus name Aegolius comes from Greek for “a bird of ill omen.” The species name acadicus refers to the historical name for the geographical location of the first collected saw-whet owl specimen, in “Acadia.” This includes parts of northeastern North America including Nova Scotia and eastern Québec.

General Description

Saw-whet owls are the smallest owl in eastern North America with a mass comparable to that of a blue jay. They have prominent tuftless round heads, “white eye-brows” a notable wide-eyed gaze and are known for their seemingly approachable and trusting demeanor. They have rufous, brown, and white plumage with mottled brown streaking on the breast, and brown tails harboring three narrow white bars. There are no differences in plumage between males and females, yet there is a large difference in size with females being about 25% heavier than males. This difference is called reversed sexual dimorphism.

Similar species: comparable to the boreal owl although saw-whets are smaller and have less spots. Eastern screech owls have ear tufts and are more noticeably streaked than saw-whets.

Fun Facts

• There is an endemic, non-migratory subspecies of the saw-whet owl that lives on Haida Gwaii, an island off of British Columbia (A. a. brooksi), that feeds on intertidal invertebrates.

• There is some banding evidence that male saw-whets may be less migratory than females.

• Larger owls such as great horned, barred, long-eared, and Eastern screech owls have been known to prey upon Northern saw-whets.

• Older saw-whet siblings are known to assist in the feeding of younger siblings after the mother leaves the nest, when the nestlings are about 18 days old.

• The oldest wild Northern saw-whet ever recorded was at least 9 years and 5 months old.

Size

| Females | Males | |

| Wingspan | 40.5-45.5 cm (16-18 inches) ✏️✏️✏️ 2-3 pencils end to end | Same |

| Mass | 70-120g (3.1-5.7 ounces) 🍋🍋 1-2 lemons | 2.5-3 ounces (70-85 g) 🍋 1 lemon |

Vocals

Nine different saw-whet vocalizations have been identified thus far, with the male advertisement call or “toot” being the most frequently heard. This call is used as a lure at banding stations to draw wild saw-whet owls in. Other vocals include begging calls, barks, wails and twitterings. Wails and “skiews” are thought to be the two vocalizations that resemble the whetting of a saw blade, and both calls are typically indicators of agitation. Saw-whet owls are typically vocally active from March through May and are thought to be relatively quiet for the rest of the year.

Habitat

Saw-whet owls reside in a variety of habitats. Although they prefer conifers, throughout their range they associate with a multitude of tree species including, from north to south; several spruces, aspen, tamarack, northern white cedar, Douglas fir, eastern hemlock, ponderosa pine and eastern white pine. Once leaves drop in autumn, saw-whets roost in conifers and evergreen shrubs or vines. There is evidence that breeding saw-whets in Pennsylvania are found in proximity to riparian areas.

Saw-whet owls roost in a variety of tree species, as well as in thick vegetation ranging from a few feet above the ground to over 30 meters (100 feet). Saw-whets seek out roosting sites that provide both thermal benefits and hiding opportunities.

Feeding

Saw-whets are rodent specialists, feeding primarily on white footed-mice, deer mice, and voles. The genus of mice Peromyscus is strongly represented in saw-whet owl pellets. Small birds (especially Northern cardinals) and insects make up a small portion of their diet as well. Saw-whets will sometimes cache extra prey in cavities or on branches.

Saw-whet owls hunt by scanning for prey from a perch, and then swooping down silently with butterfly-style wingbeats to collect their meal. Recent telemetry research indicates that saw-whets move from perch to perch and scan relatively large areas while hunting. Being crepuscular (active during times of low light), they typically engage in two main hunting periods throughout the night; one around dusk, and another before dawn. The distance between an individual’s night roost and feeding area can be up to 9 kilometers (3.5 miles). Saw-whet owls are more aerodynamic than the similarly sized boreal owl due to their lighter wing loading (ratio of body mass to wing size), which allows them to maneuver through heavy shrubbery.

Nesting

As winter ends, male saw-whets can be heard emitting their “toot” call to attract females. One a female is present, the male will bob and shuffle his way closer to the female, sometimes with a prey item as an offering. After successful courtship, females choose a nest cavity, typically targeting secondary cavities such as old woodpecker holes that average 7.5 centimeters (3 inches) in diameter. Saw-whet owls are mostly monogamous, but variations in mate structure such as polygyny and polyandry have been known to occur.

On average, egg laying falls between late February and April depending on geographical location. Clutch size ranges from 4 to 9 eggs, depending on the abundance of small mammals; an increase in prey availability means potential for a larger clutch. Incubation lasts 27-30 days. Females incubate and brood the young solo while the male does the hunting. In years of ample resources, female saw-whets have been known to leave their first clutch to the first male and start a new nest with a new male. In typical fashion of an irruptive species, saw-whets specialize on highly fluctuating prey and breeding become opportunistic as a result. Adults have no guarantee that every year will yield enough prey for successful breeding, so they take advantage of the good years to produce as many offspring as possible. The cyclical nature of rodent populations may also cause saw-whet owls to engage in breeding dispersal, shifting territories from year to year in pursuit of stable food resources. More research is needed to confirm this behavior, but we know saw-whet owls do not typically return to the same nesting site in consecutive years, most likely due to the inconsistency of prey abundance.

Migration

Saw-whet owls are difficult to study given their secretive and nocturnal behavior. However, researchers are beginning to paint a picture of this species’ annual movements, thanks to citizen science initiatives such as Project Owlnet. This collaborative project aims to provide information on the movement ecology of owls, with saw-whet owls being a focal species. The project was co-founded by acclaimed author and Hawk Mountain Sanctuary board member Scott Weidensaul.

Prior to the 1900s, saw-whet owls were thought to be a rare, non-migratory species. Now, with banding data and a several groundbreaking observations, we have learned that they are not that rare. Just like boreal owls, female saw-whets seem more inclined to migrate than males, which tend to stay on or near the breeding grounds. Like other migrating raptors that we count here at Hawk Mountain, saw-whets follow leading lines such as ridges, bodies of water, and other topographical features throughout the landscape that act as funneling structures. As nocturnal migrants, they utilize favorable winds and clear skies. Across their range, migratory saw-whets seem to time their departures with leaf drop of deciduous trees. Therefore, depending on location, autumn migration begins between September and early October and concludes by early December.

Saw whet owls travel relatively slowly compared to other raptor migrants, averaging 10.5 kilometers each night (6.5 miles), and engage in stopovers for 7 to 10 days along their journey. The number of saw-whet owls that choose to migrate each year seems correlated with the abundance of their primary prey during the breeding season, the red-backed vole, meaning large migratory flights are observed roughly every 3-5 years.

Current Conservation Status

Excessive logging, climate change, and associated loss of forest health could pose a threat to saw-whet owl populations, given their dependency on high elevation spruce and fir forests. Additionally, forests are home to a variety of rodent populations to which this owl species is tightly linked.

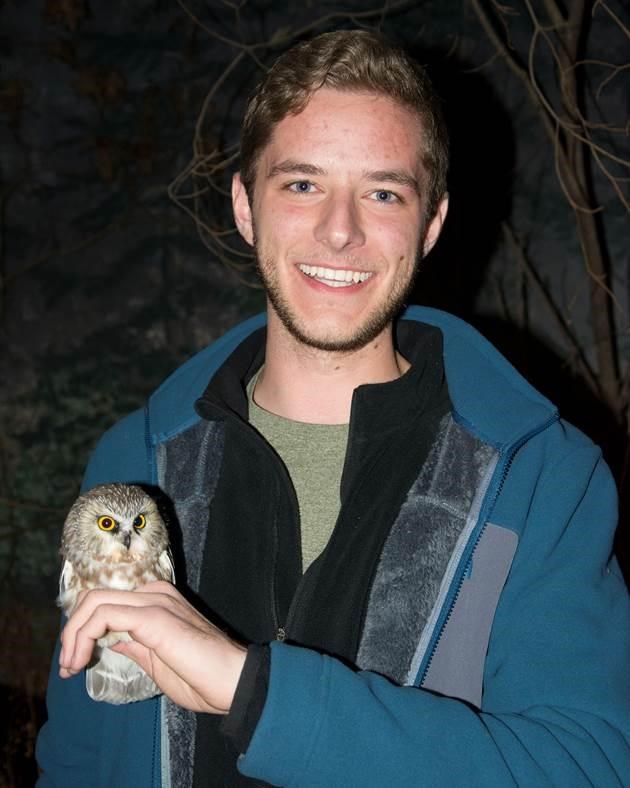

Here at the mountain we participate in a local saw-whet owl banding station by assisting with the banding process, as well as by involving our international trainees. Many of these conservationists-in-training have never seen a North American Owl, let alone one as cute as a saw-whet, and understandably their appreciation for owls is greatly enhanced after seeing one up close.

One of our former trainees, Mitchell Pruitt, completed his master’s degree on wintering saw-whet owls in Arkansas and is now building on his owl fascination through a PhD investigating dispersal and survival of North American owl species with varying movement strategies. Hawk Mountain Senior Scientist Dr. JF Therrien is serving on Mitchell’s committee.

How can you help saw-whet owls?

One way you can help saw-whet owls is by increasing the number of nesting cavities available to them, in the form of man-made nest boxes. If you think you have suitable habitat for saw-whet owls, and you’d like to help, contact Dr. JF Therrien at [email protected] for more information.

You can also spread the word that saw-whet owls, like other mammal-eating raptors, assist in rodent control. Rodenticides are extremely harmful to all raptors, and encouraging alternatives helps owls immensely.

Special thanks to Mitchell Pruitt and Traci Sepkovic for their generous photo contributions to this account.

Information written and compiled by Zoey Greenberg.

Sources

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2019). All About Birds: Northern Saw-whet Owl. Retrieved from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Saw-whet_Owl/overview

Weidensaul, Scott. (2015). Owls of North America and the Caribbean. New York: NY.: Peterson Field Guides.

Johnsgard, P. A. (1988). North American owls: biology and natural history. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.