The Red-tailed Hawk is described as a “jack-of-all-trades.”

Buteo jamaicensis

67-year annual average: 3,302

1992-2001: 3,704

Record year: 6,208 (1939)

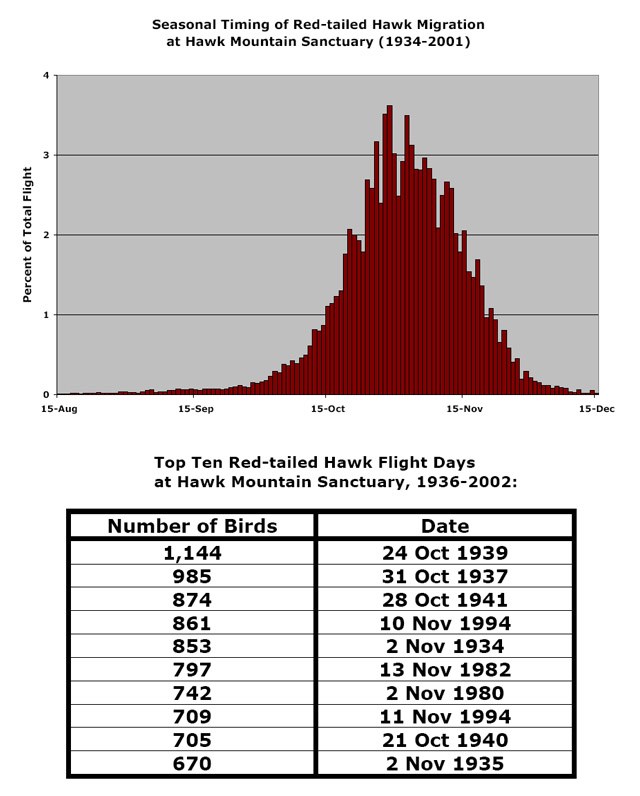

Best chance to see: Late October through early November

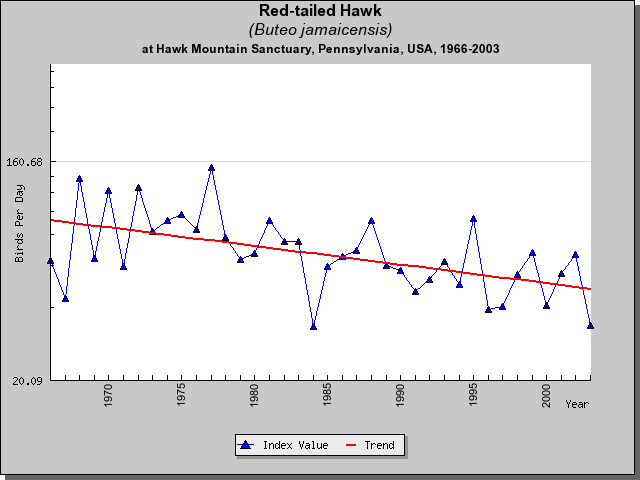

Longterm trends: Decreased in 1970s and 1980s, variable in 1990s.

Mean annual count: 3,208

Lowest annual count (year): 1,525 (1956)

Highest one-day count: 1,144 on 24 Oct. 1939

Seasonal mid-point of migration: 1 November

Early and late dates (year): 15 Aug. (1949, 1969, 1971, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1988, 1990, 1994) and 15 Dec. (1981, 1985, 1991, 1992)

Number of days it takes the middle 50% of the flight to pass: 18

Number of days it takes the middle 90% of the flight to pass: 44

Maximum rate of passage: 15 birds per hour in early November

Points of interest: From late October through early November, the daily chance of seeing at least one Red-tailed Hawk at the North Lookout peaks at 96%.

A.K.A. Redtail, Red-tailed Buzzard, Buzzard

Field marks: Chunky, light-colored, broad-winged buteo, with dark patagial marks on undersides of its wings. Generally brown above and whitish below. Some individuals have darkish belly bands. Adults have rufous tails; juveniles have barred, brownish tails.

Flight behavior: Typically migrates alone, although sometimes in small flocks.

Click below to view flyers summarizing the red-tailed hawk's habitat and nesting behaviors, as well as guidelines for landowners that may encounter forest nesting raptors:

Red-tailed Hawk Habitat & Nesting Landowner Guide to Protecting Nesting Raptors

What Size is a Red-tailed Hawk?

- Wingspan3'6"-4'4"

- Length1'5"-1'10"

- W-L ratio2.5:1

- Weight1.8-3.3 lbs

Raptor Bites

- Red-tailed Hawks are part of the family Accipitridae, which includes 224 species of hawks, eagles, vultures, harriers, and kites.

- There are 16 sub-species of Red-tailed Hawks in North America.

- Often hunt along Interstate Highways, and are sometimes called roadside hawks.

- Are the largest buteos in eastern North America.

- Often feed on carrion.

- Sometimes specialize in stealing prey from other raptors.

- Perform elaborate aerial courtship displays.

- Are usually monogamous and sometimes mate for life.

- Because of forest loss, Red-tailed Hawks have largely replaced Red-shouldered Hawks in many parts of eastern North America.

- Dark morph Red-tailed Hawks, which occur mainly in western North America, have dark brown or black plumage except for a red tail.

Seasonal Count – from North Lookout – 1934 to Date

Introduction

The Red-tailed Hawk is characterized by variability and versatility. Across its widespread range, this species exhibits remarkable diversity in plumage, habitat use, and hunting ecology, so much that the redtail is often described as a “jack-of-all-trades.” The redtail is a large, stocky buteo found from central Alaska and Canada south to Panama. Redtails are numerous migrants at many watchsites throughout their North America range. The fact that they tend to perch and soar in open habitats and tolerate human-dominated environments makes them one of the most frequently observed raptors in the region. The reddish or rufous tail of adults makes the species one of the most easily recognized raptors.

Red-tailed Hawks have adapted to human landscapes with isolated trees or small woodlots that provide nest sites and elevated perches for hunting, and their numbers have increased in North America in recent years. Human actions that have benefited the Red-tailed Hawk in the eastern United States include forest thinning and the construction of the Interstate Highway System, both of which have created prime hunting areas. In the American West, fire suppression and power lines provide additional perches for hunting.

Red-tailed Hawks also have benefited from protection from human persecution. As recently as the middle of the 20th Century, the species was blamed for losses of poultry and was labeled the “chicken hawk.” As a result, redtails were commonly shot. The Red-tailed Hawk’s propensity to perch in the open made it particularly vulnerable to persecution.

Identification

The Red-tailed Hawk, one of the largest open-habitat raptors in North America, exemplifies the classic “buteo” configuration. It has a chunky body, broad wings, and a tail that is often spread or fanned in flight. The Red-tailed Hawk’s round-tipped wings and bulging secondary feathers make the species appear “muscular” in flight. When soaring, redtails typically hold their wings in a slight dihedral or shallow “V.” In North America, the redtail together with the Ferruginous Hawk and the Rough-legged Hawk, are the only buteos that regularly “kite” while facing into the wind with their wings set.

The species varies in plumage across its range. Distinct differences exist between age groups, and among color morphs, and races. Individual redtails range from brown to black on their upperparts, and white to black underneath. The tail, which can be solid rufous, or is banded brown, is sometimes streaked or spotted. Adults typically have a reddish or rufous tail with a narrow, dark band at the tip. Compared with adults, juveniles have narrower wings and longer tails that are brownish with seven to nine dark brown bands of equal width. Dark morphs, which are common in the American West, are rare in the eastern United States. Adult light morphs have a dark brown head, back, and upperwing coverts. The underparts are pale cream or whitish with dark markings that often form a belly band. The underwings are pale with dark, rectangular patagial marks.

Breeding Habits

During the breeding season, soaring flight plays a major role in helping individuals establish and maintain nesting territories. When soaring, redtails can survey their territory and locate intruders. Migrants begin their aerial courtship displays in late winter and early spring. Sedentary birds (which remain paired throughout the year) engage in aerial displays throughout the year although most displays take place in early spring. During such breeding displays, pairs soar together in wide circles at high altitudes, and males often engage in steep dives and subsequent ascents. Males typically fly above and slightly behind the female, and sometimes the two interlock talons and spiral toward the ground.

Pairs either build a new nest or refurbish an old nest. Nests are constructed of two to three foot long branches that are usually less than half an inch thick. Both the male and female take part in nest building. When building their nests, redtails are secretive, and if disturbed, may abandon the site. Nest sites vary depending on available habitat, but in general they are open from above, and have a good view of the surrounding landscape. In forested areas, redtails usually choose to nest close to the trunk or near the tops of trees. Some individuals nest on cliffs and human constructions such as powerline towers.

Redtails lay a total of one to five eggs with roughly 48-hour intervals between eggs. The incubation period is 28 to 35 day begins shortly after the first egg is laid. The female does most of the incubation, and during this period the male feeds her. After the eggs hatch, the female broods the nestlings for 30 to 35 days, and the male continues to provide most of the food. Although both parents will bring prey back to the nest, only the female feeds the chicks. The young fledge at 44 to 46 days of age, and the parents continue to feed their fledglings for another four to seven weeks. During this time, the young gradually move farther from the nest, improve their flight abilities, and begin to hunt on their own. Some individuals remain with their parents for as long as six months after fledging.

Feeding Habits

Red-tailed Hawks are generalist predators that typically prey on small to medium sized reptiles, birds, and mammals up to the size of jackrabbits. Most concentrate their hunting efforts on species that are abundant and easily caught. As a result, redtail diets differ among regions, and across seasons, as well as among individuals. Most prey is taken back to a feeding perch where it is beheaded before it is consumed. Birds, even small birds, are usually plucked of their feathers, but small mammals are often swallowed whole. Redtails frequently feed on carrion, including roadkills.

Although Red-tailed Hawks are commonly seen soaring, they are primarily perch-hunters, and only infrequently hunt from soaring, kiting, or powered flight. Elevated perch sites appear to be a necessary component of suitable hunting habitat. A study in Arkansas indicated that Red-tailed Hawks preferred to hunt in areas with perches even though many of these areas had lower prey density than more open areas.

Migration

The Red-tailed Hawk is one of 26 North American raptors that are partial migrants.

As a partial migrant, some redtails are migratory and other individuals are not. Many redtails living in the northern portion of the species range in southern Canada and the northern United States migrate to more southerly locations for the winter. Even so, a few “northern birds” remain on their breeding territories even in the most severe winters. At mid-latitudes, many individuals stay on their breeding grounds for all or most of the winter, although some may leave the breeding territories for a few weeks in the middle of winter. In the southern United States and in Central America, most breeding birds are non-migratory. As a result, the number of Red-tailed Hawks in southern portions of the species’ breeding range increases during the winter when these areas support both sedentary residents and migratory birds.

In autumn, juveniles are usually the first to move south, and they typically move farther south than adults. Adults winter closer to their breeding grounds and migrate earlier in the spring. In eastern North America, the autumn movements of Red-tailed Hawks occur between August and early January; in spring the migration stretches from February to early June.

Red-tailed Hawks often capitalize on favorable atmospheric conditions while traveling. Like other raptors, the species begins its migration across a broad front, and thereafter concentrates along major leading lines. Leading lines emerge as migrants use or avoid features of the landscape. Redtails and other Buteos frequently soar on migration and avoid long water crossings that require sustained periods of powered flight. Favorable landscape features that concentrate migrants include long ridges where updrafts afford opportunities for slope-soaring, and manmade features such as cities where “heat islands” create numerous thermals. One leading line is the Kittatinny Ridge in the central Appalachian Mountains of eastern Pennsylvania. When soaring on ridge and mountain updrafts, redtails travel at about 30 to 40 miles per hour.

The migratory behavior of the species differs according to the time of season because of changes in weather conditions. Observations at Hawk Mountain indicate that redtails shift their migration strategy from thermal soaring in early autumn to slope-soaring later in the season as opportunities for thermal soaring decrease. As the season progresses, temperature and day length decrease, and thermal strength is reduced.

At Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, an average of 3,300 southbound Red-tailed Hawks has been seen annually from 1934 to 2001. The redtail flight generally peaks in the first week of November, and 90% of the birds pass between 9 October and 1 December. The largest flights are typically observed on the two days following a cold front when conditions are particularly favorable for slope-soaring

What are Red-tailed Hawks and how and when do they migrate at the Sanctuary?

The Red-tailed Hawk is the largest buteo in eastern North America. This widely distributed “roadside” hawk is one of the most commonly observed birds of prey in all of North America. Red-tailed Hawks are summer residents throughout most of central and southern Canada and the northern United States (including southern Alaska) and year-round residents south into central Mexico, the West Indies, and portions of Central America. With 16 recognized subspecies, this open-habitat generalist varies in plumage across its range.

Adult Red-tailed Hawks are best distinguished from other Buteos by dorsally reddish tail and dark patagial marks on the underwing. Adults are brownish above, with white mottling, and whitish to cream colored below. Many, but not all individuals, have partial belly bands comprised of dark brown streaks. Juveniles, which tend to have paler heads than adults, have narrower wings and longer, light-brown—not rufous—tails with narrow dark-brown bands. The belly bands of juveniles often are more conspicuous than those of adults. Males and females overlap considerably in size. Redtails tend to flap less, and to be more deliberate in their maneuvers while soaring than other buteos.

Red-tailed Hawks are opportunistic predators, scavengers, and piratical raptors that feed on most medium-sized mammals, birds, and reptiles. Most hunting is done from perches, although individuals also hunt while hovering, especially in regions with few trees.

Many redtails supplement captured prey by scavenging on recently killed carcasses, including roadkills. In winter, the species frequently robs smaller raptors, including Rough-legged Hawks and Northern Harriers, of their prey. Some individuals appear to specialize in such piratical tactics.

Redtails, even sedentary birds who have maintained close contact with their mate from the previous breeding season, begin courting in late winter. Courtship, which typically involves circle soaring in tandem at great heights, sky-dancing (i.e., roller-coaster flight), leg dangling, and even talon grasping by the male, occurs over a period of several weeks to more than a month. Copulation lasts from 5 to 15 secs. Redtails—especially sedentary individuals—frequently are monogamous, and sometimes mate for life.

Red-tailed Hawks build relatively large stick nests that sometimes measure 30 inches across. Nests, which are built by both members of the pair, typically are placed in the crowns of tall trees in woodlots and tree-rows, and, less frequently, in large contiguous forests. Nest-sites usually afford a commanding view of the surrounding landscape. The nest, which takes about a week to build, often is refurbished with greenery. Although many pairs reuse nests from previous years, others build one or more alternative nests in a single season.

Females lay 2-4 eggs, which are incubated by both parents, and which take from 4 to 5 weeks to hatch. Young redtails, which fledge 42-46 days after hatching, remain close to the nest and are fed by their parents for an additional 2 to 4 weeks. Some juveniles remain somewhat attached to their parents for as long as 10 weeks after fledging. Although a few yearlings breed successfully, most individuals do not breed until they are almost two years old.

Unlike several other large raptors, the Red-tailed Hawk was never singled out as a pest species in Pennsylvania. Even so, the species’ habit of perching conspicuously in open farmland habitat made it a frequent target of erstwhile game managers. As a result the redtail was considered a rare breeder in and around Hawk Mountain as recently as the late 1940s. Indeed, one prominent ornithologist claimed that their occurrence as common winter residents at the time was due, in part, to the species’ “hard-earned ability to correctly judge the range of the ever-ready shotgun” (Poole 1947). Evidence suggests that this threat has declined in recent years.

Red-tailed Hawks did not undergo large-scale reproductive failures or population declines during the DDT era earlier this century. Current threats to the species include sporadic shooting and harassment at nest sites, and collisions with automobiles and trucks.

Red-tailed Hawks have largely replaced Red-shouldered Hawks throughout much of eastern North America as forest fragmentation has created patchwork habitats favorable to the former. Overall, the species appears to be increasing its breeding and wintering populations throughout Pennsylvania and much of eastern North America.

Migration

Red-tails tend to be resident at low latitudes and migratory at higher latitudes, especially in regions of prolonged snow cover. Even so, some individuals appear to remain in the northernmost reaches of the species’ range in all but the harshest winters.

Conservation Status

The current “world” population of this species is believed to be approximately 500,000 to one million birds.

There is little evidence that redtails were substantially affected by the widespread use of organochlorines during the middle of the 20th Century. In the 20th Century, their range expanded due to increased availability of suitable habitat due to human activities, and reduced human persecution. Redtails favor open areas with patches of trees. When such areas are either further deforested or are allowed to grow into unbroken forest the number of redtails in the area is likely to decline. Automobile collisions, nest interference, and, to a lesser extent, shooting are threats to this species.

| BWHA Trends | ||

| Year Range | Trend Value | P |

| 1970-1980 | -1.9 | <0.0001 |

| 1974-2004 | -1.9 | <0.0001 |

| 1980-1990 | -1.9 | <0.0001 |

Red-tailed Hawk Reading List

ALLEN, P.E., L.J. GOODRICH, AND K.L. BILDSTEIN. 1996. Within- and among-year effects of cold fronts on migrating raptors at Hawk Mountain, Pennsylvania, 1934-1991. The Auk 113:329-338.

DUNNE, P., D. SIBLEY, AND C. SUTTON. 1988. Hawks in flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

FERGUSON-LEES, J. AND D.A. CHRISTIE. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

JOHNSGARD, P.A. 1990. Hawks, eagles, and falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

KERLINGER, P. 1989. Flight strategies of migrating hawks. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois.

MARANSKY, B., L.J. GOODRICH, AND K.L. BILDSTEIN. 1997. Seasonal shifts in the effects of weather on the visible migration of Red-tailed Hawks at Hawk Mountain, Pennsylvania, 1992-1994. Wilson Bulletin 109:246-252.

PRESTON, C.R., AND R.D. BEANE. 1993. Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis). No. 52 in The Birds of North America (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds). Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the American Ornithologists Union, Washington, D.C.

PRESTON, C.R. 2000. Red-tailed Hawk. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania.

SNYDER, N. AND H. SNYDER. 1991. Raptors: North American birds of prey. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minnesota.

STOKES D.W. AND L.Q. 1989. A guide to bird behavior, volume III. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

WEIDENSAUL, S. 1989. North American birds of prey. Gallery Books, New York, New York.

WHEELER, B.K. AND CLARK, W.S. 1999. A photographic guide to North American raptors. Academic Press, San Diego, California.