Heroes of Hawk Mountain: Female Founders

Posted on in Heroes of Hawk Mountain by Rebekah Smith, Science-Education Outreach Coordinator

As Women’s History Month comes to a close, we’d like to highlight some of the women who have had a direct hand in shaping Hawk Mountain Sanctuary’s legacy. From its inception, women have laid the foundations for Hawk Mountain Sanctuary’s global impact, which began on a modest swath of land in South Central Pennsylvania and consequentially led to global raptor conservation, fueled by the hard work and courage of many women in conservation. Today, Hawk Mountain Sanctuary follows their example by training young women in conservation and contributing to raptor research by supporting female leaders in ornithology through grants, publications, and outreach. The strong women in Hawk Mountain’s story have taught us to be resilient, to stand up for what we believe in, and to share our passion for the natural world with others. We hold each of these women and others who have helped to shape Hawk Mountain Sanctuary’s heritage close to our hearts as we continue to work toward our mission and our ultimate goal of protecting birds of prey world-wide.

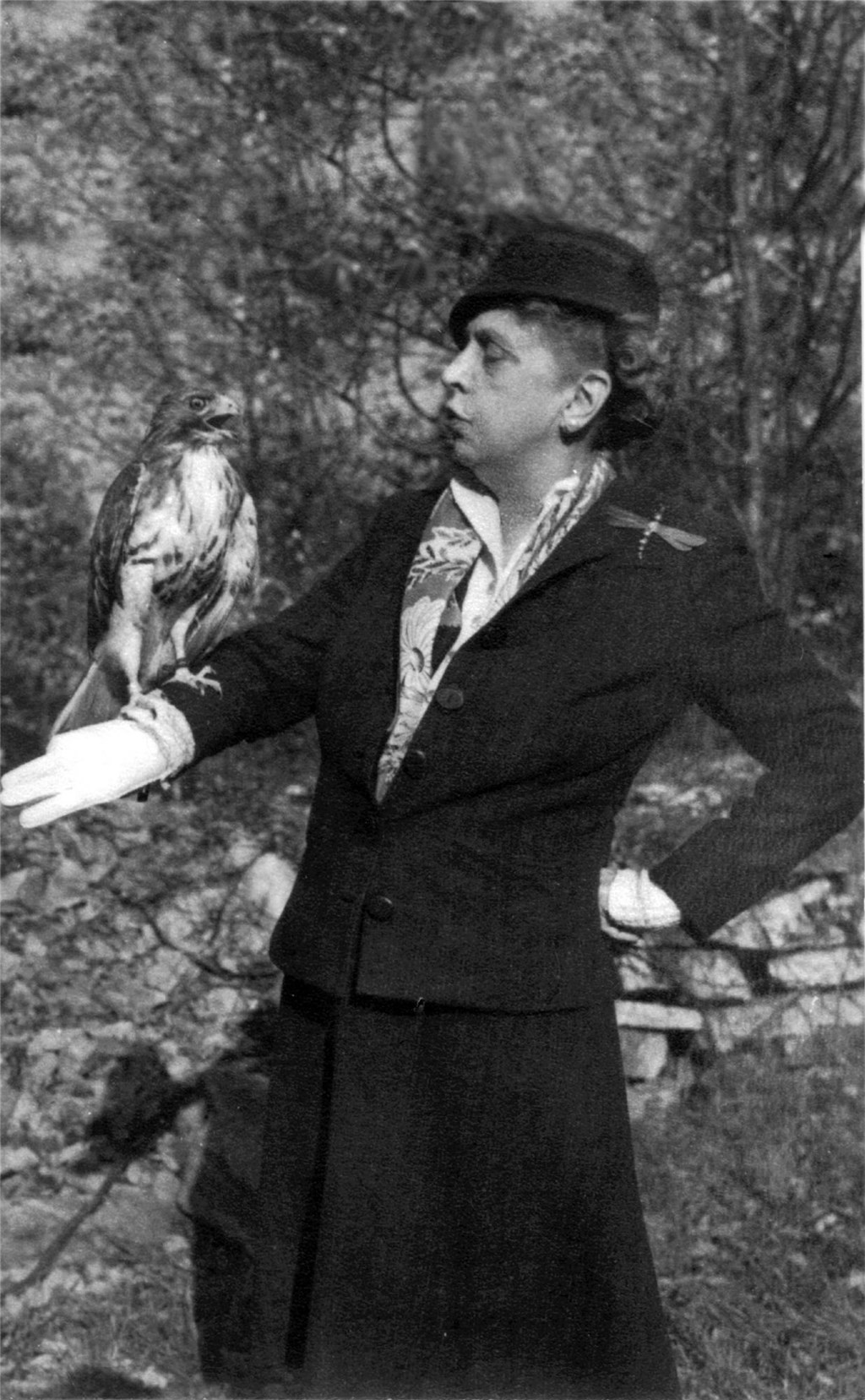

Rosalie Barrow Edge

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary’s founder, Rosalie Edge, was a women’s suffrage champion, as well as a groundbreaking conservationist. She was born into a wealthy New York family, allowing her to live a comfortable lifestyle, travelling and studying as a young adult. Her activism began in her mid-30’s, while pregnant and traveling back to the United States from a trip to Asia. For the first time, Rosalie learned of the women who were fighting valiantly for women’s right to vote in the United Kingdom through a brutal process of strikes, protests, and violence. She was inspired by their story and wanted to bring the fight back to the United States. After having her second child, whom she named after Margaret Mackworth, a prominent UK suffragette whose story had stirred her interest in the women’s suffrage movement, Rosalie decided to act. She quickly joined the Empire State suffrage movement and became a member of the publicity committee of the New York Suffrage Party. During her first two years of involvement, her duties included writing pamphlets, distributing them on the streets of New York City, and speaking publicly to encourage men to vote for women’s suffrage.

Her pamphlets read, “Since the war began. women's suffrage has been sweeping over the civilized world. Women are now voters in Canada, in Russia, Norway, Finland, and Denmark; they are about to become voters in Great Britain; all constitutional liabilities have been removed from them in Holland; and government bills to give municipal woman suffrage are under way in France and Italy. The women of New York state have no less patriotism, courage, or ability than the women of England, Russia, or Canada. They ask the men of New York to recognize this and vote for women’s suffrage on election day.”

Rosalie also marched in protests through the streets of New York City along with thousands of other women in the movement, while donning a golden and white striped banner that read “VOTES FOR WOMEN” and “WOMAN SUFFRAGE PARTY” in bold letters. She kept this banner close to her, among her most prized possessions, tying her to the passionate spirit of activism she experienced during the women’s suffrage movement. She modestly wrote that her role in the women’s suffrage movement taught her to “stand up at meeting”. Ultimately, it forced her to be militant and stand her ground, skills that would later become outstanding qualities that allowed her to breathe life into a stale conservation movement.

New York became the first Northeastern state to win women’s right to vote on November 6th, 1917. Once Rosalie finished her first battle, she was ready to lead the next. After reading about the killing of thousands of bald eagles in Alaska for bounties in 1929, she directly confronted the National Association of Audubon Societies about their complacency on the matter. Not receiving a satisfactory response, Rosalie took matters into her own hands. She joined forces with a zoologist working for the American Museum of Natural History, Willard Van Name, and founded the Emergency Conservation Committee, where she again mobilized her activism through writing and distributing pamphlets. A photographer brought to her attention the Pennsylvanian tradition of shooting raptors during migration in exchange for bounty money, and Rosalie chose to act. She raised the money from supporters and procured a loan from Van Name to lease the 1,400 acres that became Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and, in doing so, created the world’s first refuge for birds of prey.

The Emergency Conservation Committee lasted for 32 years, through the Great Depression and World War II. They published dozens of pamphlets and helped to reform the Audubon movement and establish Olympic and Kings Canyon national parks. Though her opposition would discredit her by pointing out her suffragist experience and highlighting her limited conservation background, Rosalie was described as “the only honest, unselfish, indomitable hellcat in the history of conservation” by her colleague, Van Name. Rosalie’s journey symbolizes the intersectionality between the women’s suffrage movement and the conservation movement that occurred during the 20th century. She was one of the first women to permanently leave a mark in conservation history, and her legacy will live as long as the mountains she left it on.

Irma Knowles Penniman Broun Kahn

Newlywedded Maurice and Irma Broun were hired by Rosalie Edge, becoming the first wardens and protectors of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary after its leasing in 1934. The couple was tasked with defending the lookout from hunters, encouraging them to lay down their guns for pairs of binoculars. Irma Broun will always be known as the first gatekeeper, defending the migrating raptors by stopping hunters with ill intentions before they could make it to the lookout. Though this charge was integral in the establishment of the world’s first sanctuary for birds of prey, Irma was so much more than Keeper of the Gate. Prior to meeting Maurice, she spent time studying at the School of Practical Art in Boston, traveling, and had been enrolled at the D.D. Palmer School of Chiropractic Medicine in Davenport, Iowa.

Irma discovered her love for birdwatching when she met Maurice, who had been working as an ornithologist at Cape Cod's Austin Ornithological Research Station. While dating, she and Maurice would sneak out in the middle of the night to watch roseate tern colonies and search for heron rookeries together. Choosing to accept the live-in Sanctuary warden position with Maurice soon after their marriage was an act of true bravery and sacrifice during a time when wardens had been threatened, harassed, and even killed for preventing bird poaching. Irma readily accepted her position as Keeper of the Gate, despite hesitation from Rosalie and Maurice.

"Our lives were endangered for about three or four years. They shot over our heads and told us to leave, but we never did leave," Irma said in 1994.

"Anyone who came along and had a gun, I told him he couldn't go up there," she recalled. "One day a big hunter came up and got out of his car, and he had a gun and his beagles along, and I told him it was now a bird sanctuary and they wouldn't allow hunting.”

"He said, 'Who's going to stop me?' and I said, 'I am.' And he said, 'And how are you going to do that?' I said, 'I have a gun, and I know how to use it.' And he turned and walked back to his car and went away."

Besides being a fierce gatekeeper, Irma became the sanctuary’s first educator, greeting guests with information about the trails and the seasonal migration. Irma endured the hardships of living atop Hawk Mountain without electricity or running water for nearly two decades, but she was always in good company. She enjoyed inviting hundreds of students and birdwatchers for dinners and extended visits. Irma also brought some of her Boston art school education with her to the Sanctuary, painting beautiful landscape portraits of North Lookout and Appalachian Trail thru-hikers.

Maurice wrote of Irma in Hawks Aloft, “My wife was fortunate in the choice of her forbearers. They were pioneers in the best New England traditions: They were venturesome, independent, and courageous seafaring people. They were masters in the art of handling people. So, my wife came naturally to her role as Keeper of the Gate.”

Maurice and Irma never had children together. The duo was known as a conservation power couple by all who met them. Her friends referred to her as a “very, very independent” woman. She remained an avid conservationist throughout her life and continued to spread the word about Hawk Mountain’s conservation work even after Maurice passed away and she moved to California.

Sue Robertson

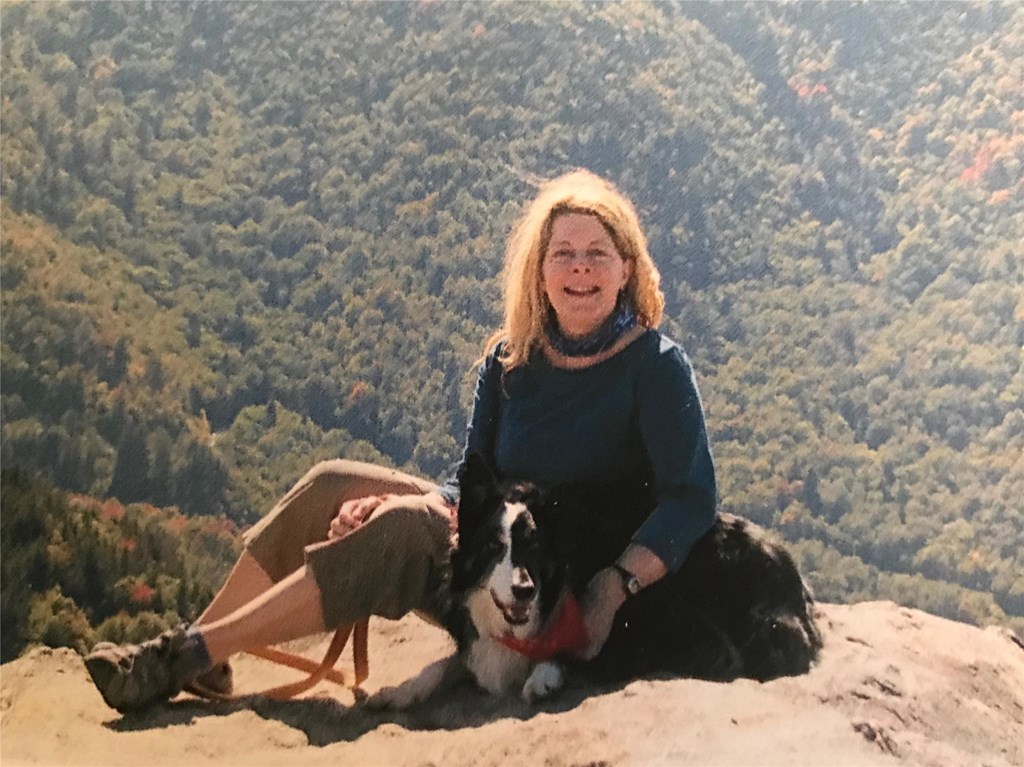

Volunteer and citizen scientist Sue Robertson, now in her 90s, has helped to ensure the success of the long-term American kestrel nest box study at Hawk Mountain and in Florida for decades. Sue's work monitoring local populations of American kestrels in the Kempton Valley began with her husband, Bob, more than 40 years ago and continued after Bob passed away. Their establishment of the Hawk Mountain long-term monitoring kestrel nest box program represents one of the longest running, consistent nest box monitoring program in existence.

A skilled raptor researcher in her own right, each summer she tended to the many boxes that surround the Sanctuary, banding, weighing and measuring nestlings, and working with our staff and trainees to collect and track data. She even spent winters in Florida where she caught and banded adult kestrels near Fort Meyer's. Sue estimates that she likely has banded more than 3,000 kestrels in her lifetime.

Together with her husband, our staff and others, Sue also has co-authored several papers on her findings. Her consistent and methodical recording of kestrel nest box data over the last four decades has allowed current and past trainees, interns, graduate students, and staff to answer many questions about American kestrel survivorship, behavior, and other aspects of their ecology. Even today, Sue’s maps and nest box routes are used by Hawk Mountain staff and graduate students to ask new questions about American kestrel ecology and carry on the research that began with her dedication.

Hawk Mountain is thankful to Sue for her years of dedication and contributions to science. She has been an inspirational role model for all of us.

Cynthia Lenhart

"My career in conservation began in 1983 on Capitol Hill as a lobbyist for the National Audubon Society. Several older female colleagues served as inspirational role models for me there. I travelled the country interviewing national wildlife refuge managers about their priorities and testified before Congress about appropriations for endangered species recovery and refuge land acquisition. I served as Chair of the Everglades Coalition, a consortium of national, regional, and local organizations focused on the rehabilitation of that ecosystem and was a founding board member of the American Bird Conservancy.

In 1990 I accepted the position of Executive Director of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, becoming the first woman to occupy this role. My Audubon experience influenced my leadership style, which was more of team building than top-down approach. I hired many talented people, some who are still members of the staff, and encouraged them to run with their ideas. In my 14 years at the Sanctuary, we expanded our land holdings by over 200 acres, created the Acopian Center for Conservation Learning, and developed an international network of raptor conservation sites.

I credit my leadership success, in part, to my female mentors who taught me by example that a good leader is self-confident enough to allow her staff the room to develop and contribute. Looking back at all we accomplished, I am proud to have been instrumental in the evolution of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary."

Christina Clayton

"An English major in college, a lawyer, and a woman, my path to Hawk Mountain Sanctuary was not a typical one. While I loved the outdoors, my encounters with raptors as a child were strictly in books about ancient Egyptian iconography. Horus was a favorite.

My mother, Nancy Clayton, introduced me to raptors in the wild. After I left my parents’ home, she became a volunteer hawk counter at Wachusett Mountain in Massachusetts, secretary of the Hawk Migration Association of North America (HMANA) and a serious collector of books about raptors of the world, many of which are now housed in the Acopian Center at Hawk Mountain.

When I first began hawkwatching, DDT had just been banned and peregrine falcons that hatched at Cornell’s Lab were released at several sites on the East Coast and were beginning to reproduce in the wild. Osprey were also making a comeback. One of the most thrilling moments of my life was the first time I saw a peregrine falcon in flight as it rounded a bluff at Block Island, Rhode Island. After that sighting, my husband and I missed only one autumn hawk migration season over a period of almost forty years. The sight of a male northern harrier, the “gray ghost,” flying down from the North Lookout in a November dusk is indelible in my memory. It’s hard to articulate the many things that the hawk migration has been for me, but the word rapturous is one that comes immediately to mind.

It has been a privilege to serve on the board of directors and gain an inside perspective on the work of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary’s outstanding conservation science, education, and stewardship staff. My husband and I have also had the opportunity to give financial support to multiple nascent research projects. We have most recently supported the study of the decline of American kestrels, led by Dr. JF Therrien.

It has been thrilling for me to watch Hawk Mountain Sanctuary train young female scientists, who, as a result, emerge and shine in the field of raptor science, a field that was traditionally occupied by men. I was thrilled to witness the passing of the Sarkis Acopian mantle from Dr. Keith Bildstein to Dr. Laurie Goodrich, and now, to view presentations and read papers authored by strong, smart, and self-confident women from all over the world taught to conserve raptors by Drs. Goodrich, Bildstein, and Therrien. How appropriate that Hawk Mountain Sanctuary—founded by Rosalie Edge, a woman who has attained almost mythic status in the world of conservation due to her vision and actions—would help launch the careers of these extraordinary women. I thank the Hawk Mountain community for welcoming me into its midst."