Land of the Sky Clowns

Posted on in In the Field by Zoey Greenberg, Science Outreach Leadership Trainee

King vultures are ridiculously handsome scavengers. When one of these color collages fixes you with a bright yellow gaze it’s akin to locking eyes with a sky clown, though somehow the moment feels un-funny. True to their name, they carry an air of royalty that is impossible to ignore and as a species, they are a breathtaking compliment to the diversity of the natural world.

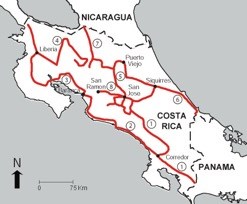

I saw my first king vulture this month in Costa Rica, as I joined senior research biologist JF Therrien and former trainee from 1999, Pablo Porras, to assist in Hawk Mountain’s vulture surveys as part of our ongoing population assessment study. On this trip six surveys were completed, covering a wide expanse of Costa Rica’s rich and diverse habitats and updating our web of vulture knowledge by furthering our understanding of their winter movements. We also succeeded in confirming a collaboration with the non-profit Osa Birds: Research and Conservation, in which two annual vulture surveys will be completed by director Karen Leavelle and her crew.

There were many a day when the note taker (often me) remained in a constant state of scribble-frenzy as vultures swooped literally everywhere, and while neck cramps became my constant companion, they were worth the discovery that this year’s numbers were plentiful. In total, 2,785 vultures were counted! Turkey, black, and yes, king vultures were recorded as were other raptors, such as road-side hawks, black hawks, yellow-headed caracaras, and crested caracaras. The next step is to compare the numbers recorded in our 2019 surveys with surveys conducted in 2006. Hawk Mountain and its partners intend to repeat vulture surveys in many regions of the Americas in the next few years.

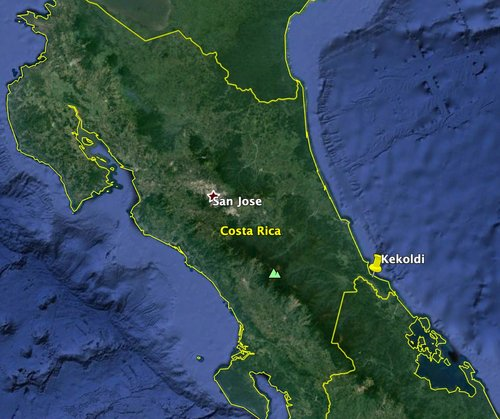

Costa Rica is part of an important geographical bottleneck that funnels migrating raptors to and from South America. During the early 2000’s there was a raptor count site called Kekoldi located on an indigenous reservation close to Puerto Viejo. Kekoldi was run by Pablo from 2000-2006, and our own Dr. JF Therrien volunteered there as a counter, returning on this trip for the first time in sixteen years.

To revisit the site, we hiked from a lodge built and run by Sebastian Hernandez, a member of the Cabeca tribe, up to a tower built by Sebastian himself using trees from around his home. After climbing four flights of wooden steps our heads popped into sky surrounded by canopy, butterflies, chattering toucans, and eye level turkey vultures. Only moments later we caught the silhouettes of double-toothed kites, black hawks, white hawks, and a fascinating turkey vulture mimic, the zone-tailed hawk. All of these birds and more, in February.

Kekoldi and the Costa Rican migration corridor see one of the top five highest counts of migrating raptors in the world, and one of the most numerous peregrine falcon flights in the Americas. The Kekoldi tower was built with the intent of hosting visiting scholars, educators and enthusiasts from local communities and internationally. Regretfully, financial support became a limiting factor all too soon, and after a count of six years there were no longer resources to keep the tower manned each season, although sporadic counts are occasionally conducted.

Many cutting edge studies are illustrating the need for understanding of species’ annual cycles, and this means investigating multiple hotspots along their journey. The Costa Rican Caribbean flyway is part of the migration pathway for many North American birds. Perhaps with greater outreach in raptor conservation, those with the knowledge and passion to start another count site may be inspired to do so. When that day comes, raptors throughout the Western Hemisphere will have higher chance of survival through their long migratory journeys in the years to follow because as we have learned, monitoring and education are a powerful duo that when used properly, can change the trajectory of conservation.

In addition to surveying vultures, Another intent of our visit to Costa Rica was to explore the possibility of promoting the importance of raptors within schools. Hawk Mountain is already partnering in Veracruz Mexico to promote environmental education and outreach and has been for more than 25 years. Our hope is to extend the raptor conservation message by providing materials and training throughout this critical flyway.

There are approximately twenty schools near the Kekoldi count site that already receive outreach from the Talamanca-Caribe Biological Corridor, overseen by the country’s Ministry of Education. This organization is a well-established and respected facilitator of nature engagement for public schools in the area. During our visit we received a positive response from their education coordinator about the possibility of inputting a Hawk Mountain generated raptor component into their future programs. The intention would be to contribute materials such as children’s books, lesson plans, posters and interactive activities that would fit the needs of local schools, and prove useful within their community’s environmental reality.

On my final day at the tower I contemplated the strong undertow of the country’s natural history. Tropical creatures danced and shuffled by in erratic circles as we kept our binoculars skyward, waiting for a raptor to carve figure eights in the clouds above. Our hope is that one day this experience will be available to others, and that visitors will be able to engage in their very own sky clown moments, solidifying in their minds the majesty of the tropics and the beauty of the raptor world.