Thar She Soars!

Posted on in In the Field by Zoey Greenberg, Science Outreach Leadership TraineeZoey Greenberg, Science Outreach Leadership Trainee

Many people associate the term “birder,” with images of a khaki-clad, hat-wearing, field-guide holding, binocular-wielding, mud-splattered nature enthusiast carrying a massive camera and an intense look on their face that says “SHHH…did you hear that?” Of course, there are many types of birders (I myself bird, and wear exactly one of these items), but to those unfamiliar with the lifestyle, a birder should be dawning the appropriate materials to claim the term. Imagine then, trying to explain to a police officer that the reason you are pulled over in someone’s lawn staring at their house with binoculars is because you are, in fact, birding. You are not wearing khaki, there is no mud on your pants, but you do have a camera. He does not believe you. The camera does not help your case. This is what we call a predicament.

Such a circumstance is one of the amusing side effects of conducting road surveys to monitor vulture populations. Hawk Mountain has been doing this over the last 12 years, gradually collecting baseline data on both turkey and black vulture populations throughout the Western Hemisphere. Our protocol involves following roads that are least likely to induce rage from other drivers (we drive 40 miles per hour, and frequently swerve to hop out and count birds on cell towers, sometimes climbing the car for optimal vantage points). We need at least two people, a reliable vehicle, and enough time to accurately gather data. Ideally we conduct these surveys every 10 years in both summer and winter, for each site. Compared to other research projects, road surveys are a good bang for the buck because they are relatively cheap to conduct but provide us with critical baseline data on a group of animals that are crucial to the health of our environment. In total, Hawk Mountain has conducted over 50 vulture surveys in 9 countries.

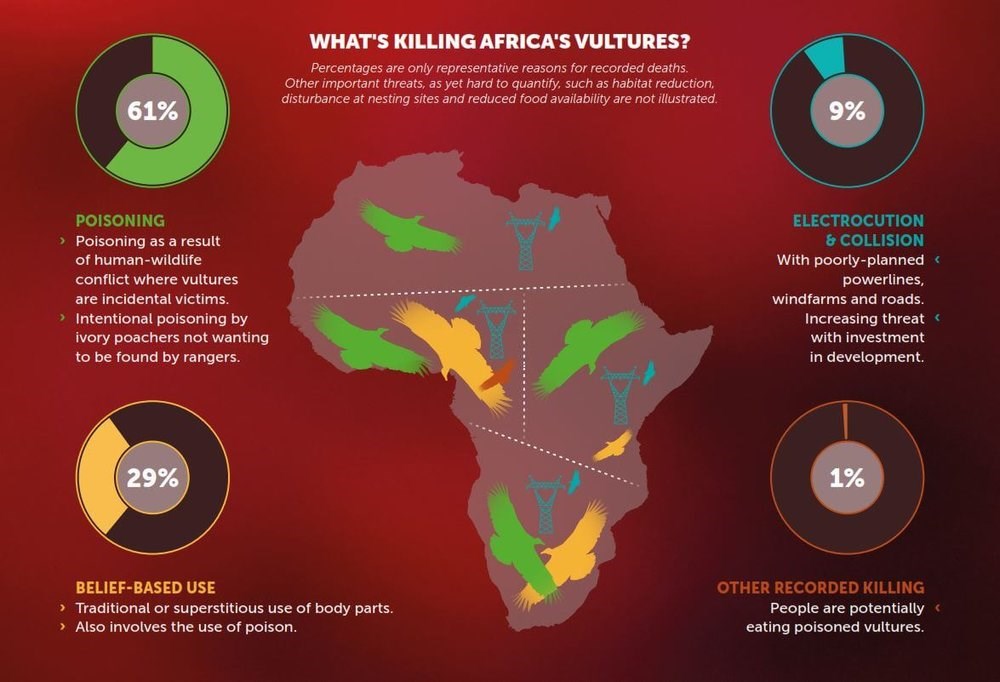

Many of you may be aware of the vulture crisis that has occurred in the Old World over the last two decades, but I’ll offer a reminder by first reviewing the numbers: out of the world’s 22 species of vultures, 16 are spread among Africa, Asia and Europe. 11 of these have recently become at risk for extinction in our lifetime. Some species have experienced a 99% decline since the late 1990’s.

With the combined effects of persecution, poisoning, drug-induced kidney failure, and harvesting for parts, the Old World has faced a fast-acting recipe for vulture disaster.

In Asia the primary cause of these mass die offs is a pain killer for cattle called Diclofenac that is ingested by vultures feeding on livestock carcasses.

In Africa the main threat is poisoning. In Europe, Diclofenac is still legal, and declines are anticipated if policy-makers don’t act quickly. There is a less harmful alternate drug available that offers the same therapeutic effects for a similar price,but so far, new legislation has not been passed.

Prior to the declines recorded in Asia and Africa there was no reliable baseline knowledge on the population size of affected species, meaning estimates of loss are likely conservative. Consequences from loss of vultures have included an increase in rabies cases due to a higher prevalence of wild dogs, as well as the spreading of diseases that were previously processed in the gut of these under-appreciated scavengers.

This is a perfectly heart breaking example of how human bias towards the most lovable species can sometimes harm those that float under the radar. To make this mistake once is somewhat forgivable. To make it twice is not.

This is why I believe Hawk Mountain’s vulture surveys are crucial. Vultures have been misunderstood and ignored, and while there have been commendable efforts to remedy this issue in Asia, Africa and Europe, we still have work to do in the Americas. We need to be proactive in deciphering how many vultures there are, fully understanding their role within our shared ecosystems, and proving their value to the public. Science alone cannot prepare us. The integrity of our future environment requires that we establish a culture of appreciation around vultures that will allow them a seat at the ecological table.

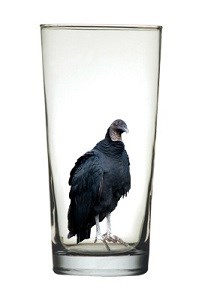

Okay, that’s the heavy part. Now, let’s focus on the fact that in the U.S., our vulture glass is half full. Our last survey resulted in a count of 979 vultures, between five routes in Georgia and Florida. Ten years ago, this same survey produced similar numbers, proving stability exists within that region. We continue to witness healthy numbers of black and turkey vultures throughout Pennsylvania and much of the eastern United States. This may not be the case in Central and South America, though our upcoming surveys in Costa Rica, Panama, and Argentina will hopefully add to our body of knowledge on population size and trends.

On one of our final days in Florida, we spotted a group of vultures circling something yellow and indistinguishable. A scout landed and tore into whatever “it” was. After scanning with binoculars, exchanging excited hypotheses, and crossing a treacherous road, we discovered that the mysterious yellow “entrails” were no more than the sad remnants of a Happy Meal. This not only confirmed my suspicion that vultures are closet vegetable lovers but also reminded me that scavengers are adaptive problem-solvers. Black vultures in Central America drag coconuts into the middle of the road and wait for cars to pulverize them into a meal. We hear of crows and ravens using tools, eagles stealing fish from other birds, and raccoons breaking into, well…everything. Scavengers are scrappy, and vultures are no exception. This gives me hope that with support, they will adapt to our ever-changing human dominated environments.

As we watched the sun set behind the french fry frenzy, I felt optimistic that with continued monitoring my innovative feathered friends would have many more happy meals.