The Mystery of Pennsylvania's Lesser Black-backed Gulls

Posted on in In the Field by David Barber, Research Biologist

We stood around the back of the pick-up truck tearing up day old bread, cookies, and muffins into bite-sized pieces. When we thought we had enough, Pennsylvania Game Commission biologist, Patti Barber, grabbed a bag and walked to the middle of the vacant parking lot and started tossing pieces into the air. Within seconds ring-billed gulls came flying in to take advantage of the free meal. But these gulls weren't the reason we were all gathered on this cold March day at Nockamixon State Park. Patti was after lesser black-backed gulls.

Lesser black-backed gulls have captured the attention of Pennsylvania's birdwatchers ever since they first started showing up in winter in southeastern Pennsylvania in the 1960’s. You see, lesser black-blacked gulls do not nest in the United States and these birds typically appeared in November and disappeared in March. Where were these birds coming from and where were they going? Armed with 10 satellite transmitters, Patti along with biologists from the Game Commission, Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, and Hawk Mountain Sanctuary hoped to find out.

While the ring-billed gulls were not shy about coming into the buffet, the lesser black-backs were more aloof, standing off to the side of the food scrum, just outside the range of the rocket net. They had to come into the center of the feeding frenzy in order to fire off the rocket net. By moving around with the food Patti was able to manipulate the flock's movements.

By late afternoon, the flock finally moved so the lesser black-backed gulls were in the target zone. With a boom the net arced out over the gull flock ensnaring nearly 80 gulls, a mix of ring-billed, herring, and lesser black-backed gulls. Everyone mobilized, releasing the ring-billed and herring gulls and saving the prize, 20 lesser black-backed gulls. By the time all of the gulls were released, the sun was setting and the cold was seeping into our fingers. Not willing to simply release our captives, we needed to need to find a warm, bright spot where we could band the birds and attach the satellite transmitters.

We drove back to our house, turning the garage into a make shift banding station. The immature gulls were measured and banded, while the adults received both a band and a satellite transmitter. We finally finished processing the last bird at 2 am and caught a little sleep before driving back to Lake Nockamixon to release the birds at sunrise.

According to Patti, the transmitters are providing a wealth of information, the birds don't just spend the winter at Lake Nockamixon, but often commute to different water bodies in southeastern Pennsylvania and central New Jersey, including Green Lane and Peace Valley reservoirs in PA and Spruce Run and Round Valley reservoirs in NJ. Some even spent time on the NJ shore before commuting back to Lake Nockamixon.

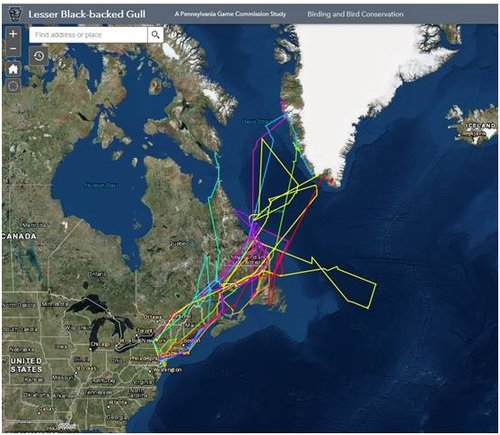

And where do these birds go in the spring? Of the 9 birds that were tagged with transmitters in 2018, one transmitter stopped working before the spring migration, but five of the birds spent the summer in Greenland and three spent the summer in Quebec, Labrador and Newfoundland, Canada.

As of early February, six of the gulls returned to southeastern PA, one was wintering in Virginia, but is heading north to PA and one transmitter failed on the breeding grounds. An additional satellite transmitter was deployed on an adult bird last week and is hanging out at the New Jersey reservoirs.

Thanks to the Pennsylvania Game Commission with help from Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation and volunteers, we are well on our way to solving the mystery of Pennsylvania lesser black-backed gulls.

Visit the Game Commission's Lesser Black-backed Gull project page for updates as they become available.