Turkey Vulture Life Histories Revealed

Posted on in In the Field by Wouter Vansteelant, Visiting Scientist

I saw my first Turkey Vultures in March 2011 when driving from the Newark airport to Hawk Mountain. I had been invited by Keith Bildstein to work on a paper about raptor migration along the Black Sea coast of the Republic of Georgia. It was my first visit to the USA, and during the weekends of that spring I frequently marveled at the Turkey Vultures soaring through the Kempton valley. Little did I know that I would come back to Hawk Mountain to study Turkey Vulture migration six years later.

It's been about 7 weeks since I arrived, and one of the most exciting things I've been able to study here so far is undoubtedly the life-history of David. David was part of a family of four Turkey Vultures (2 chicks and their parents) to be tagged in an old farmhouse in Saskatchewan in 2013. Out of four Turkey Vultures that have been tagged as fledglings in Saskatchewan, David was the only one ever to reach adulthood, allowing us to map the entire life-history of a Turkey Vulture from fledging until adulthood the first time.

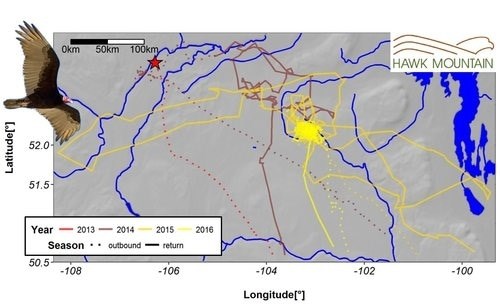

After leaving the nest (red star) David did not spend any time exploring the surrounding area. Instead, the first time he left the immediate surroundings of the farmhouse was when he departed on his first outbound migration (red track). Although he did not migrate with his parents, he left around the same time as other Turkey Vultures breeding in Saskatchewan and found his way to Central America. He then returned to Canada in spring 2014 and spent most of the summer making extensive exploratory movements without settling in a clearly defined area (brown track). In August that year, David passed within a few miles of the farmhouse where he hatched the year before. His mother had died during spring migration but his father was breeding again in 2014. David, however, did not visit his natal site and spent a few days along the river 20km SW of the farmhouse before initiating his 2nd outbound migration (dotted brown track). When David returned in 2015 he quickly settled in an area approx. 240km ESE of his natal site. He made some long exploratory movements in early summer but spent most of the summer in the same area (orange track). In 2016 David then returned directly to the same area and spent the entire summer there (yellow track).

David's movements suggest he was breeding for the first time in 2016. Unfortunately this could not be confirmed in the field, but David is still alive and transmitting today. We cross our fingers for his safe return to Saskatchewan this year, so that local birders can try to connect with this bird in the field and confirm his breeding status.

David is one of a few wild vultures in the world for which the entire life-history could be recorded by satellite-tracking. As such many open questions remain, not in the least regarding what factors drive the decision of individual birds to settle in one area rather than another. These questions can only be answered by satellite-tracking many more vultures throughout their entire lives, and connecting with these birds in the field across the entire flyway as frequently as possible.

I hope Hawk Mountain will be able to track many more juvenile vultures in the year to come, and wouldn't mind to come back another year to help with analysing the data.

---

You can follow Wouter at @WMVGs on twitter to keep up with his latest finds.