Migration Along the Corridor

Raptor Migration

Each fall, many North American raptors migrate thousands of kilometers south to wintering grounds in tropical habitats, stretching from Mexico to South America, in search of food and shelter. Wind and thermals power their flight, and prey helps to fuel their migration. To survive the journey, hawks must be in good physical condition, maximize their travel distance, and save energy along the way. High mountain ranges, oceans, and lakes present obstacles for migrants and concentrate the birds into narrow pathways.

The graphic below illustrates the impressive journey migrating raptors take through North and South America each season.

The migration journey is long and can be dangerous. Some raptors fly individually, but many gather in large flocks that migrate together over a short period of time. Raptors are solitary most of the year but flocking allows them to take advantage of ideal flight conditions and allows people to observe great numbers of these often secretive, large, and impressive birds in flight. However, the large concentrations can make them vulnerable to conservation threats.

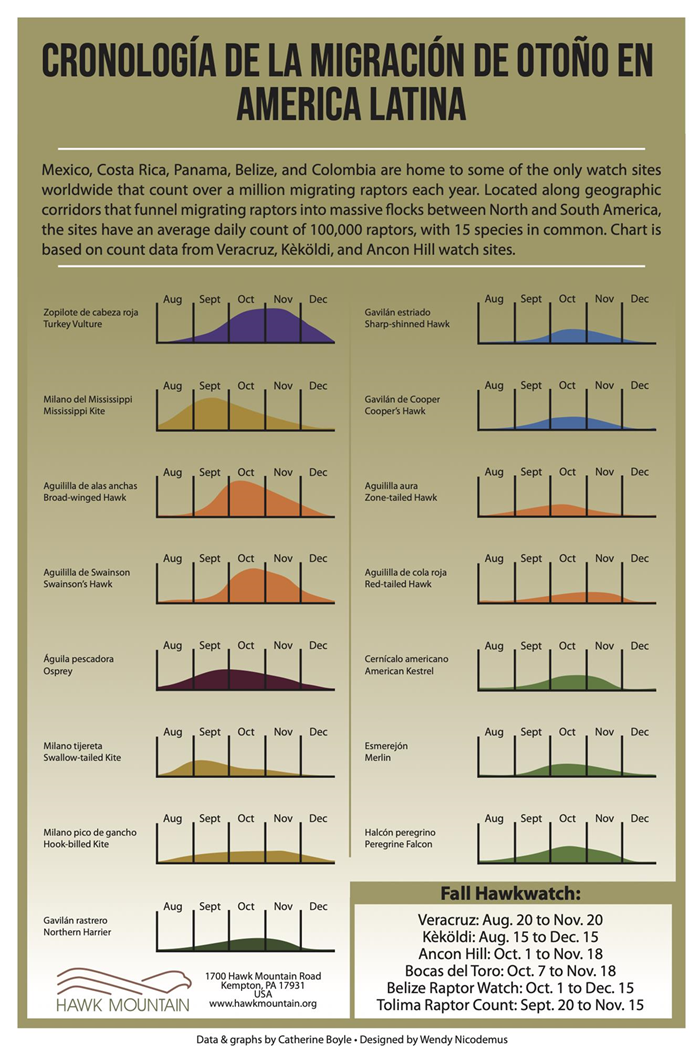

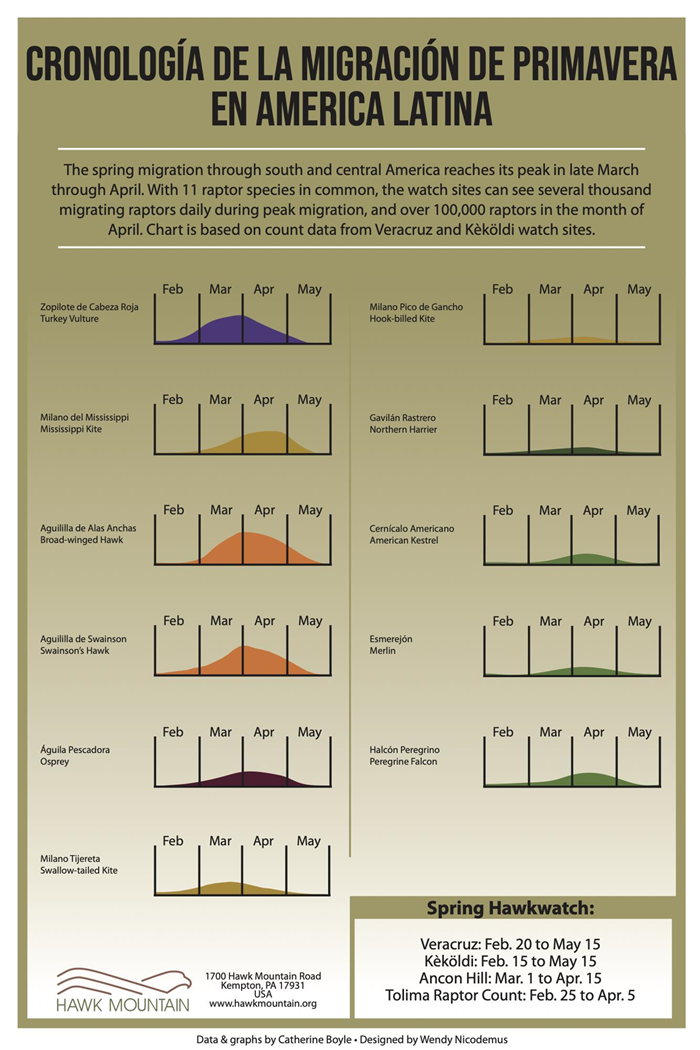

Migration Timing

Weather, the starting point, and destination of the journey determines when a raptor migrates. Mississippi kites that nest in southern United States pass over southern Mexico as early as August, while the last migratory turkey vultures originating from Canada may reach the Colombian Andes by mid-December.

Weather impacts seasonal prey availability, which in turn affects migration timing. By late summer the number of insects decrease in the southern United States and insect-hunters such as the Mississippi kite begin to move, following and feeding upon the large numbers of butterflies and dragonflies that are also migrating south. Soaring raptors that feed upon small mammals, such as the northern harrier, delay migration until cold weather limits hunting success. Powered-flight raptors, such as the peregrine falcon, merlin, Cooper’s hawk and sharp-shinned hawk, feed on birds and may move south when large flocks of songbirds vacate the north.

The timeline of migration by season in Latin America is shown below.

How Raptors Migrate

Different species use different strategies on migration. Relatively large-winged species, such as eagles, vultures, and buteos, migrate by soaring on updrafts and thermals, saving energy, and moving long distances in one day. Some soaring migrants travel up to 480 km in one day and avoid crossing large bodies of water. They follow longer, indirect routes over land where updrafts and thermals occur consistently. In the narrow corridor of Central America, raptors funnel through in large numbers, making this area critical to their conservation.

Falcons, ospreys, and harriers frequently use more active, flapping flight allowing these birds to take a straighter, more direct route across both land and water. The peregrine falcon can travel from northern Canada to Chile. Some cross the Gulf of Mexico or travel through the Caribbean islands while others stay over land. Many raptors, including accipiters, use both soaring and flapping flight.

Thermals and Updrafts

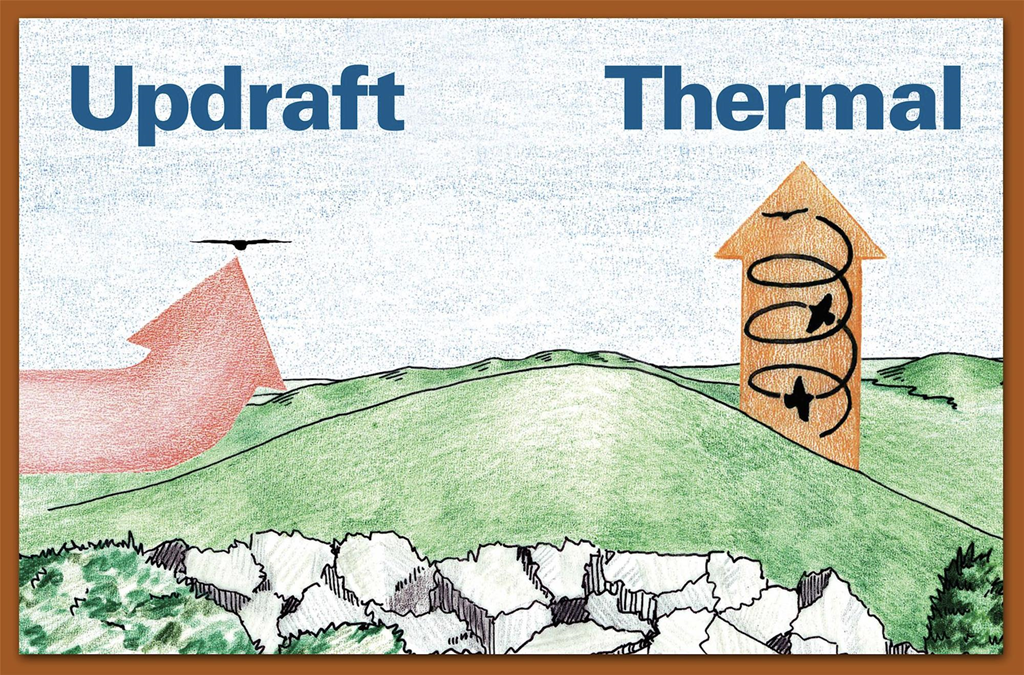

Traveling long distances demands energy. Prior to migration, some hawks gain as much as 10 to 20 percent of their body weight in fat to fuel the journey. Raptors conserve energy by soaring—using rising currents of air to gain lift and fly with little flapping.

Raptors “slope-soar” by riding winds deflected up and over hills and mountains, or “thermal soar” by circling in pockets of rising, warm air called thermals. Thermals are created when the sun heats the Earth’s surface. Hawks can quickly rise thousands of meters within thermals and then glide effortlessly in the direction they are moving. Studies suggest that some raptors can migrate several thousand kilometers without using much energy when soaring in thermals.

Land Conservation for Migrants

Habitat protection is critical to the survival of migratory raptors. Some raptors hunt throughout their journey in the early morning or late afternoon and will rest for several days at a time during migration. Other raptors may go many days without feeding, relying on fat stores, or feeding on flying insects enroute. For example, almost the entire world’s population of Swainson’s hawks travel more than 10,000 km, from as far north as the temperate grasslands of western Canada to winter in a small portion of the Pampas region of Argentina and Uruguay. Most of them pass through Central America in a narrow window of time in fall and spring. To fuel their journey, they access several stopover sites during their migration where they feed on grasshoppers and other insects allowing them to complete their long trip. Healthy grasslands or pastures with insects are as important as forest habitats to roost and rest.