"Vulture Restaurants" aid field work

Posted on December 10, 2015 in Science

By Keith L. Bildstein, Ph.D.

Sarkis Acopian Director of Conservation Science

9 December 2015

Together with African colleagues and Hawk Mountain research associates, I have been studying the “Critically Endangered” hooded vulture for going on three years. The work is beginning to pay off. I have just returned from 10 days in the field in and around Kruger National Park in northeastern South Africa where temperatures soared to 108 °F, and I have much to report.

As of early December 2015 we have placed satellite tracking devices on four “hoodies” in The Gambia, four units on birds in Ethiopia, and nine units on birds in South Africa. We also have placed “camera traps” at a number of hoodie nests in South Africa, as well as at several “vulture restaurants” there. Initial results at the latter are fascinating. But first some background…

Hooded vultures in Kruger National Park, South Africa

This summer, a second round of roadside counts in The Gambia indicated that hoodie populations there continue to do well, with numbers in the western part of the tiny African nation hovering at an astounding 15 birds per square kilometer, a density that makes the region home to the highest population of hooded vultures anywhere. Unfortunately, things are not nearly so good in South Africa where roadside counts in Kruger National Park, a supposed stronghold, indicate a population of far less than a single bird per square kilometer. My field work in South Africa earlier this month also produced close-up looks at more than 10 active nests in private game reserves immediately west of “The Kruger,” where nests along some sections of the Olifants River are sometimes as close as 100 meters or less.

Our Conservation Colleagues

As in any collaborative endeavor, working with the right people makes all the difference and the Sanctuary’s hooded vulture studies in South Africa are not exception. Kerri Wolter at VulPro (a vulture NGO outside of Pretoria), consistently offers up exciting results and insights regarding hoodies breeding in the Olifants River Private Game Reserve. And Andre Botha at the Endangered Wildlife Trust (an NGO in Johannesburg) is doing likewise for birds breeding and feeding in The Kruger, as well as several adjacent private reserves. Dr. Marc Bechard at Boise State University continues to help with trapping and harnessing hoodies with satellite tracking devices, as well as helping on road counts within The Kruger.

The newest addition to the South African team, Dr. Lindy Thompson, a Post-Doc in the Department of Biology in at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, adds an additional level of excitement and expertise to the team. On the job for less than a year, Lindy is following the nesting successes and failures (baboons and a hail storm appear to be responsible for at least some of the latter) of a number of hoodie nesting pairs in private reserves west of The Kruger.

Vulture restaurants assist in tagging

Lindy also has initiated studies at several “vulture restaurants” in the region, where human provisioning of hoodies and other vultures with offal and assorted body parts of domestic animals slaughtered at local abattoirs, is helping the birds meet their daily caloric needs. Although such provisioning can disrupt the normal behavior of avian scavengers, human “nutritional assistance” at vulture restaurants provides “clean” food to birds in areas where poachers have been known to purposely lace with poison the carcasses of rhinos and elephants they kill for their horns and tusks. Their intent is to kill the vultures, whose flocking behavior often alerts game rangers of poachers’ activities.

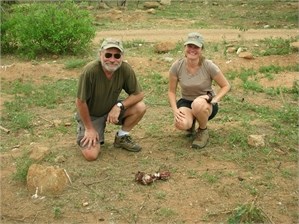

The Selati trapping site

Having spent considerable time in the field at a vulture restaurant last week, I now have a much better understanding of how hoodies and other vultures use the restaurants, as well as of the benefits of such sites in providing close-up looks at several of our satellite- and wing-tagged individuals. The vulture restaurant at the Selati Game Reserve, for example, routinely attracts dozens of hoodies, with attendance on some feeding days reaching 25% or more the regional breeding population. And indeed, I managed to visually locate two of our satellite-tracked birds at the site–both of which appeared healthy. (Actually, our tracking records indicate that four of the nine birds we are tracking visited the site while I was there.) Later this month Lindy and Andre plan to trap and measure up to three additional hoodies at this important site and place satellite tracking units on them.

Trapping birds at the Selati site and, possibly, at other restaurants will help speed our wing-tagging and satellite-tagging efforts and also will provide us with much needed information on the health of individuals captured and examined there. Given the precarious nature of the species in South Africa, the restaurant work may make all the difference in helping us offer solutions for better managing this declining population.

Finally, Lindy plans to visit Hawk Mountain’s Acopian Center for Conservation Learning for several months this spring, at which time the two of us will begin to analyze tracking and nesting data already collected. Plans for 2016 also call for me to make two additional trips to Africa or field work in South Africa and The Gambia.

No one has assembled a better team of vulture specialists and is working as hard as we are to protect this globally endangered species and I very much look forward to keeping you up-to-date with our field efforts in the coming months.

Do not hesitate to contact me by phone (610-781-7358610-781-7358) or email ([email protected]) if you are interested in supporting our work.

Until then, all the very, very best, Keith