Autumn 2019 Leadership Trainee: Circumpolar Ecology with Olga Kulikova

Posted on December 24, 2019 in Science

By Rebekah Smith, Science-Education Outreach Coordinator

Kolguyev Island is a Russian Island located in the south-eastern Barents Sea. It has a diameter of 50 miles and mainly consists of wetlands, bogs, and some glacially formed hills. There is only one inhabited settlement on Kolguyev, further emphasizing the true wilderness of this place. In its tundra-esque environment, Olga hid behind piles of rocks and tufts of grasses watching for a rough-legged hawk to fall for her carefully placed trap. When she finally catches one, it is tagged and equipped with a transmitter. Kulguyev is also an arctic field station, where Olga conducted research for five years. During her time there, she regularly filled out a questionnaire created over 30 years ago by the Zoological Museum of Moscow University. Olga has also visited and worked at four other arctic field stations similar to this one, where she contributed to the standardized questionnaire database. This standardized questionnaire has been the inspiration for her current study, which will shed light on the highly disputed topic of predator and prey peak fluctuation in the arctic.

Kolguyev Island is a Russian Island located in the south-eastern Barents Sea. It is also an arctic field station, where Olga conducted research on arctic species for five years and regularly filled out a questionnaire, creating a database of observations. Olga has also visited and worked at four other arctic field stations similar to this one, contributing similar data. This standardized questionnaire has been the inspiration for her current study, which will shed light on the highly disputed topic of predator and prey peak fluctuation in the arctic.

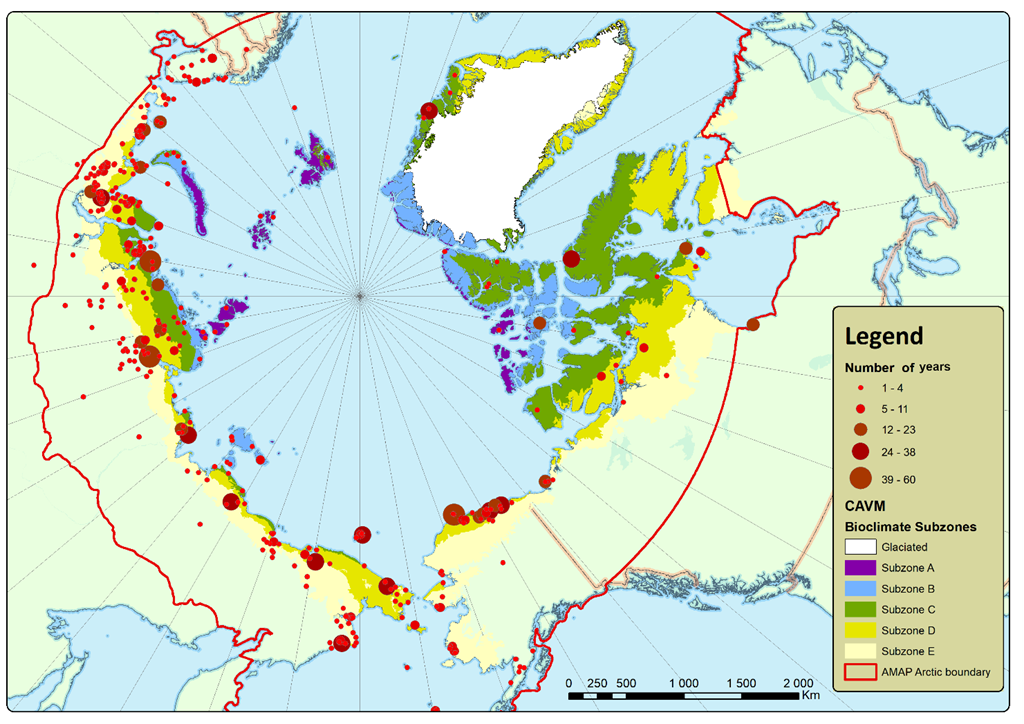

Olga arrived on the Mountain in September and has since been working closely with our senior scientist, Dr. JF Therrien, to process a data set compiling records from the questionnaires spanning more than 30 years, five countries, and 396 arctic research sites. “These sites hold untapped ecological records that can give us long term insights into food web interactions” Olga shared during her presentation at the Acopian Center for Conservation Learning with fellow trainees, staff members, and board members. Her enthusiasm for her work was palpable as she attempted to explain her research goals within the confines of a few short minutes. Researchers spend hundreds of hours at these field stations collecting data for their own individual studies, but they also collect background information about the environment while in the field using the questionnaires. To Olga, this information is extremely valuable.

Olga, originally from Russia, is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Konstanz, Germany. She has partnered with the Max Plank Institute for Animal Behaviour and is a researcher for the Institute of biological problems of North Magadan, Russia. She began working on her PhD in April 2017 and has been working in collaboration with Hawk Mountain for this project which will become one of three papers she needs to complete her PhD. Breeding ecology of arctic raptors is a topic that aligns perfectly with Dr. Therrien’s arctic raptor research, and Olga feels as though she is learning from the best. In her words, “JF seems to be really excited about my research as well, every time I come to him with some new results he wants to help me follow the lead.”

Olga’s study stems from a long line of research disputing the boom and bust of rodent populations in relation to the boom and bust of predator populations in the arctic. So long in fact, the argument dates back almost a century. Rodent booms used to happen at a more reliable rate – about every four years or so. However, within the past three decades, rodent population spikes have been less reliable, sporadic, and even absent. Some of these declines have been owed to climate change in recent studies. It is generally accepted that arctic predators relied heavily on the cyclic nature of rodent population peaks for reproduction. Yet there are still important questions that have not been answered. Is this food-web top-down or bottom-up? Do predators seek out rodent peaks? Are rodent peaks really controlled by predators? Additionally, no one has been able to provide long term data that shows predator reproduction rates during rodent population peaks and crashes. Olga’s research attempts to address these questions and more.

Olga has been using a statistical analysis program called R which uses coding commands to process data. Many ecologists love to work with R because of its versatility and availability. With R, Olga has taken data from the 396 arctic research sites and preformed a logistic regression, which has helped her to determine the connectedness between populations of predators and populations of prey. She has been looking at predator species abundance and predator species breeding status in relativity to rodent abundance. The predators she has chosen to analyze are arctic foxes, rough-legged hawks, snowy owls, and pomarine jaegers. All four predator species have circumpolar distribution and have been known to rely on rodent abundance as a food source.

Olga has found that arctic foxes and rough-legged hawks breed regardless of rodent population. However, the pomarine jaegars and the snowy owls suffer reproductive reduction when rodent populations crash. She found that snowy owls were not breeding in 99% of cases when rodents are rare. This means that snowy owls are the most sensitive to rodent peaks and crashes. Additionally, rough-legged hawks have always been seen as rodent specialists, but her data suggest that they may be more generalist. Her data also highlights the lack of snowy owl population research because it suggests that they may be less prevalent compared to other predators. She hopes that her work can help to unravel some of the mysteries of the arctic, an important task, especially in the face of an era of unpredictability due to anthropogenic climate change.

During her time at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary Olga was able to complete her data analysis and the first draft of her paper, which she hopes to send out to co-authors over the holidays. She and JF have high hopes for what they’ve found and can’t wait to see the final product through to journal publication. Even though Olga enjoyed her visit to the world’s first and oldest raptor sanctuary, she is excited to travel home to be with her husband and her Chesapeake Bay Retriever named Falc. There’s no doubt that the three of them will soon be off on another arctic adventure.